The sun rises on another hot Friday morning in Kirkuk, about three hours away from the city of Mosul in Iraq. The weekend is just about to start — shopkeepers in the bazaar downtown are starting to file in and set up their stands for another day of work. Minding their business, they are unaware of the threat that is already on the loose in their city. The offensive against Daesh in Mosul has been underway for several days now, and by all accounts it has been going according to plan. Until this Friday morning in Kirkuk, that is.

On October 21, at four in the morning, heavily armed gunmen arrived in Kirkuk on the back of a truck. They had reportedly snuck into the city from Hawija, in Daesh’s territory southwest of Kirkuk. By dawn, Kirkuk’s security forces were on high alert. Rumours swirled that as many as 200 armed Daesh operatives were roaming the city.

Then, piercing the morning air, bullets and explosions hit the marketplace. The blast in the bazaar was so powerful it left molten shards of metal strewn on the streets. For hours, a dramatic battle was underway between an elite Kurdish counterterrorism squad and Daesh fighters holed up in an under-construction hotel. While they concentrated on the showdown at the centre of Kirkuk, attacks hit several points around the outskirts. One of those was the Shuhada district, nestled in the city’s majority Kurdish northern side.

An off-duty reserve soldier in the Iraqi Kurdish peshmerga army, Sherko Zangana was reclining on his couch flipping through the channels that morning. When he saw the live footage of the carnage at Sanubar Hotel being broadcast on every television channel, he grabbed his Kalashnikov and stood guard outside the front gate of his home. After a few quiet moments, he noticed his cousin Hemin standing outside. Within an hour, there were six men on the block doing the same. Tense, they kept their hands on their rifles and their eyes on the end of the street as they heard gunshots from the next street over.

“We all thought Kirkuk was safe,” Sherko says. It had been more than a year since the last attack, when a surprise assault killed a high-ranking Iraqi commander and sent the city into chaos.

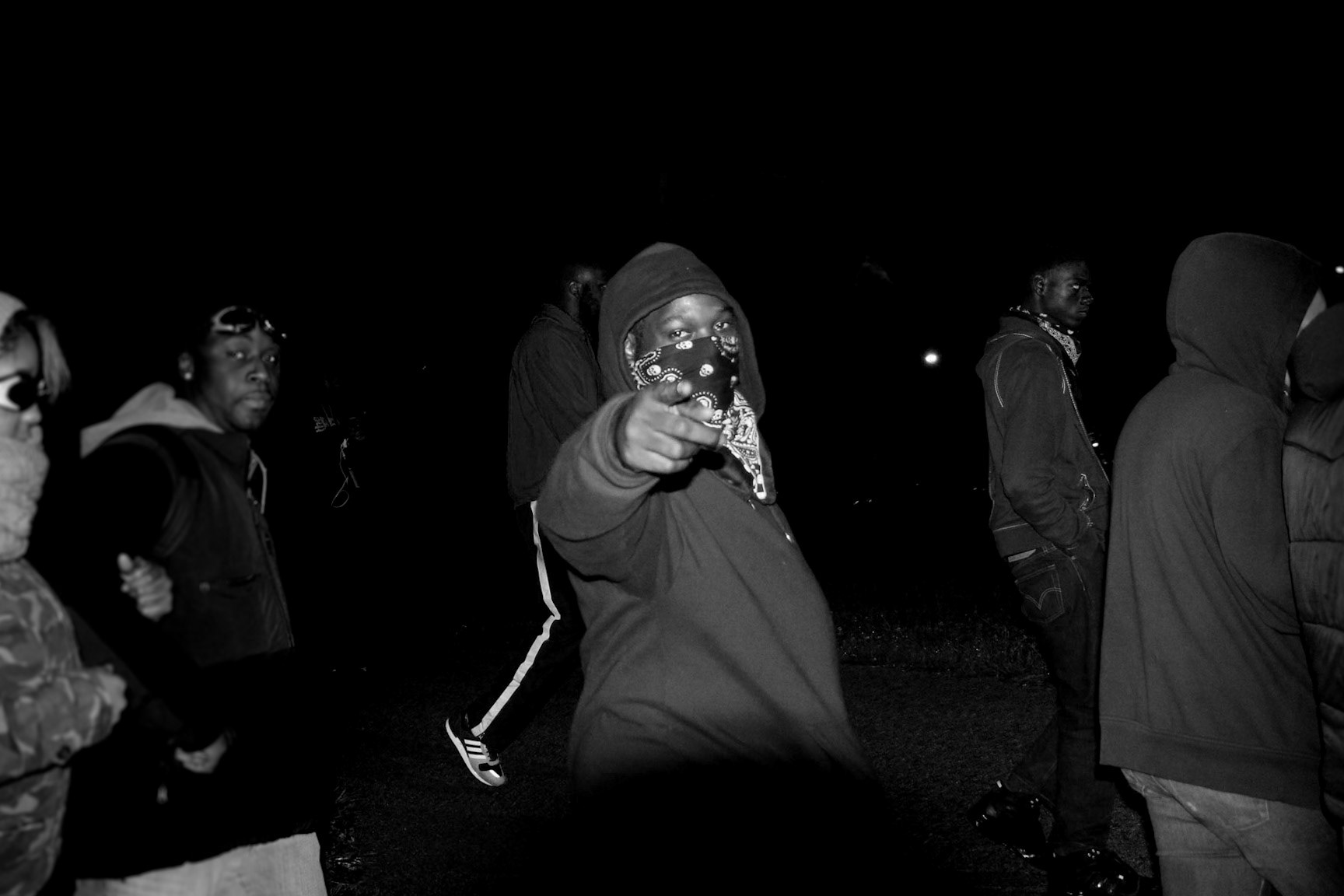

Thinking a Daesh attacker could be hiding around any corner, the men of Shuhada district decided to take their safety into their own hands and formed a neighbourhood watch — an informal group to patrol their streets. These volunteers — some with military experience, some without — assisted the local police and security forces in clashes with Daesh throughout the city on the day Kirkuk was attacked. Since then, they’ve become a semi-regular presence, gathering at night as a show of force and community resolve against Daesh.

I meet Sherko in front of a candy shop in Shuhada district about a month after the attack. He’s now the de facto captain of a loosely-organised group of men who patrol two square blocks near where the clashes took place.

Their group doesn’t have a name — no uniforms, ranks or any type of official status. They’re simply a group of young men who live on the same street and, facing a threat, decided to take up their own weapons to secure their own corner.

“Every man is ready to fight to defend his family. So we had to be ready for them, so Daesh wouldn’t come for us in our sleep,” Sherko says.

The group agrees to take me on a tour around Kirkuk to watch them work.

We pile into Sarkar’s small Mercedes and drive around the city. I sit in the back seat, in the middle, where there’s barely enough room for everyone’s legs, and their guns. Sherko hangs out of the open trunk in the back of the car.

They take me to a residential street just off a busy intersection to show me the site of their stand-off with Daesh. Walls and cars just beside a school are pockmarked with recent bullet holes. The entrance of a metal workshop stands charred and shredded by a grenade thrown by one of the Daesh gunmen who stormed the area on that bloody Friday in October.

The men hastily jump out of the car and scan the periphery. The eager gaggle of gun-toting volunteers draws attention from passers-by. As the men strut around recounting the heyday of their battle with Daesh, they are welcomed with familiarity by residents. Saman, the group’s tall and handsomely shaved unofficial spokesperson, greets a man walking by, exclaiming, “There’s the guy who saved my life!”

They take me to the home of a man who lives near Friday’s battle site. Inside, the kitchen cabinets have been torn apart by bullets from the fierce battle on the street. Mustafa shows me a back room where he, his wife and four children hid while the terrifying scene unfolded just outside. There is a newly-plastered wall at the back of the house, still wet. Mustafa explains, “We could heard the shots inside the house, and we were sure they were coming for us. We were panicking, so we broke down the wall to escape — I just put up the new wall yesterday.”

The watchmen — four Kurds, one Arab and one Turkman — see themselves as non-political protectors; just a regular bunch of guys who are trying to keep their own neighbourhood safe. “We would never use violence unless it was to protect people. If we did, then we would be no better than Daesh,” Saman told me, as the men smiled approvingly at him.

They are six, but they used to be seven. Hemin Zangana was killed by a Daesh fighter, also on October 21. Sarkar, who was with him, ducked behind a wall during the shoot-out. Hemin was in front. When he stood up to take aim, a burst of gunfire felled him.

Sarkar and Huseyn show me the exact spot where Hemin died. For all the pride these young men take in the new responsibility they shoulder, the loss of one of their own is sobering. They pay attention when the conversation revolves around Hemin, and it seems to have hit them hard, though they struggle to hide it.

None of the others were related to him, but his surname, Zangana, comes from one of the largest tribes in the Kurdish region. “He was probably my cousin,” Sherko tells me, standing next to the wall where Hemin died.

The toughest of the bunch goes by the nickname “Kanka” — he carries the biggest gun, and the personality to match it. Kanka struts around with a loud pair of sunglasses that seem to be too big for his face, chin up as if to keep the shades from falling off. Aggressively, he steps onto the road to stop traffic and allow a flock of schoolchildren to cross the road.

I ask the gentle giant if he has any brothers, “I’m my mother’s only son,” he responds, “but I always wanted a little brother.”

Idrees wears a bandage on his forehead. It’s an unassuming wound, but when I ask him how he got it, his calm response betrays a harrowing memory. “Daesh shot me in the head,” he says, matter-of-factly. “My head was tipped back; I was looking up at the sky and the bullet just tore through the ripples on my forehead. You can’t imagine what was going through my mind after that moment.”

As we pass Al-Aarouba district, everyone in the car tenses up. “We won’t take you there,” Sarkar says. “In that neighbourhood, they sympathise with Daesh,” he continues.

Al-Aarouba looks like any other street in Kirkuk — except for the black flags lining the street. While it’s possible there may be sleeper cells waiting to launch an attack on the city at any time, as happened on October 21, Daesh isn’t the only group that uses black flags. They are commonly used by the Shia Muslim community to demarcate their areas of influence among the city’s complicated political topography. They could also signify mourning.

The men’s distrust of the area may have more to do with the ethnic and sectarian puzzle that is Iraq. Kirkuk is located within territory disputed between the federal government in Baghdad and the autonomous Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) headquartered in Erbil, in the country’s north.

When Daesh overran the country and captured Mosul in the summer of 2014, the central government in Baghdad lost its grip over Kirkuk. The KRG’s peshmerga forces took control of the city, seeking to secure and expand the borders of the autonomous Kurdish region.

Neither Kurds nor Arabs are a majority in the diverse city, but tensions linger among those loyal to Baghdad and those loyal to Erbil — both are resentful of one another for the country’s violent deterioration. Even though most Iraqis would call Daesh their enemy, religious communities do exist among them which would sympathise with the idea of a government based on Islamic law — though not necessarily on Daesh’s extreme interpretation of it.

At night, the watchmen gather on the corner before starting their patrol shifts. There isn’t much organisation to it, and not much ground to cover. The six of them form a huddle and decide who will man either end of the main street demarcating the extent of their neighborhood.

They pace with their rifles, nodding at familiar faces, and occasionally waving down cars to ask where they’re going. More a show of force than professional security measures, it’s their presence that they hope will be an effective deterrent for any would-be attackers in their neighbourhood.

The six men maintain friendly relations with the local Asayish or security police, and operate with their unofficial permission. A police truck stops by to deliver a bag of dates and a few bottles of cola. The captain thanks Sherko for reporting a suspicious car a few days earlier, which resulted in the arrest of a man storing explosives in his home.

Kids eating ice cream float by on hoverboards past the armed men on watch as the night winds down. A tentative peace has returned to Kirkuk, allowing people to breathe easy and feel the distance between their homes and the battle in Mosul. The group hasn’t seen much action since the day Daesh struck Kirkuk. The night patrol vacillates between an urgent mission and a casual chat on the street. Simply, standing outside in public and claiming space seems to somewhat alleviate the tension brought on by the active conflict against Daesh just outside the city.

“It’s kind of fun, actually,” Sherko tells me as the night winds down. He’ll stay on the overnight shift with three other men, in pairs of two. With a smile, he tells me, “Before, I didn’t talk to my neighbours very much. But now we’re working together on something. We look out for each other.”