Amid conflict in Syria, stifled free speech and oppressive machismo, rappers in Turkey are speaking out to hold their country – and themselves – to account

Pop culture is usually a comfortable distraction, but sometimes it can wake you up.

Take the Turkish rap epic Susamam, which translates as "I Can’t Stay Silent:" a 14-verse manifesto for a generation fed up with complicity, and the largest collaboration in the history of Turkish rap. For a quarter of an hour, 19 artists challenge a litany of social issues, ranging from domestic violence to animal rights and police brutality. It got 20m hits on YouTube in the first week alone.

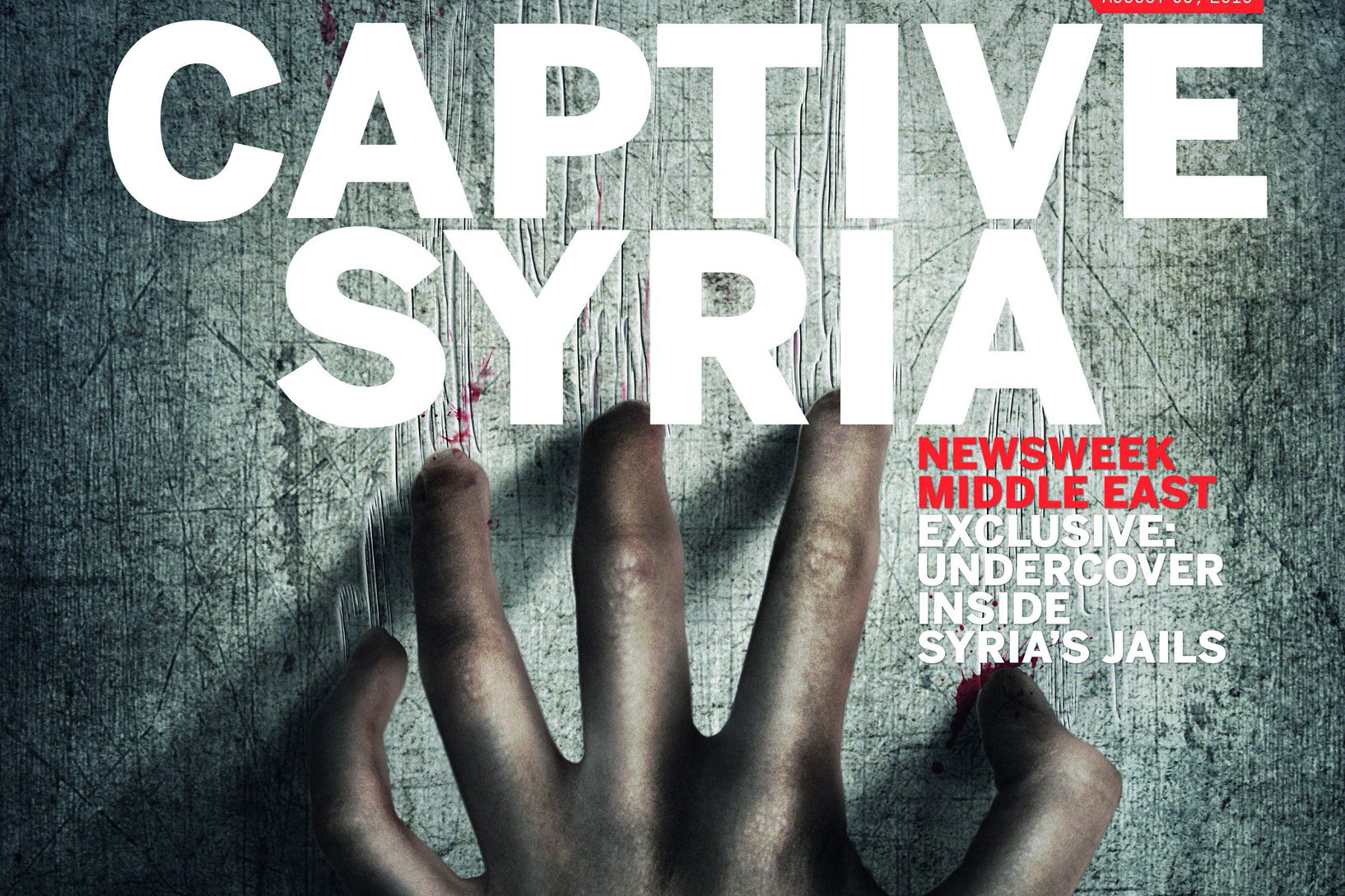

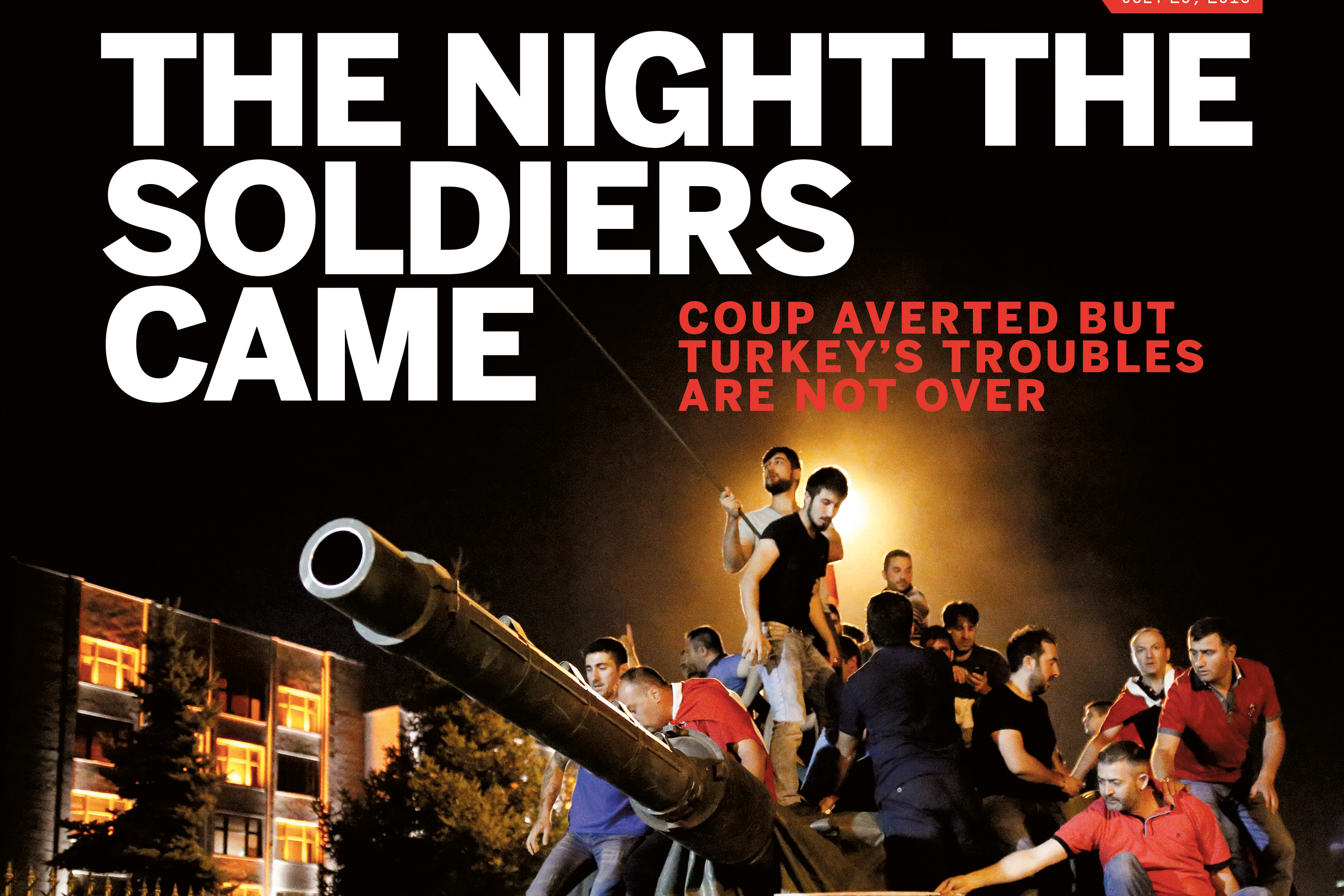

What makes the track even more impressive is the climate in which it was born: Turkey’s record on freedom of expression has taken an abysmal turn in recent years. Turkey is now the top jailer of journalists worldwide, and tens of thousands have been imprisoned in political witch-hunts that followed a failed military coup in 2016. With the nation now in active conflict in neighbouring Syria, it is common to see daily news reports of people jailed for something as simple as social media posts – even posting messages opposing war is considered support for terrorism.

In such a stifled climate, Susamam prompted widespread acclaim and condemnation. Turkey is no less polarised than Brexit Britain or Trump’s America; Susaman has been lauded as a protest anthem by some, and labelled a “terrorist co-production” by one pro-government tabloid. And its creative mastermind doesn’t even have a record deal.

Rapper Şanişer, who spearheaded the collaboration, says: “My first reaction was genuine sadness, for the state of my country, of the world. I did this project to unite people, because these are everybody’s problems. They’re global issues we all face every day.”

The video begins with two relatively innocuous verses about human arrogance when it comes to destroying the environment, before going straight for the jugular. Set behind prison bars, Şanişer fires back at a cellmate shocked at how citizens watch their every step, fearing the police: “Innocent men rotting in jail without knowing why? It’s all your fault! / This horrifying picture is your creation / Corrupt MPs, getting rich leeching on the backs of the poor / You sat by and called killers ‘justified’ because they are cops / You didn’t say a word, which means you’re guilty / Now the ‘justice’ you thought would protect you will come knocking at your door / When they falsely arrest you one night / No journalist will report it – they’re all imprisoned.”

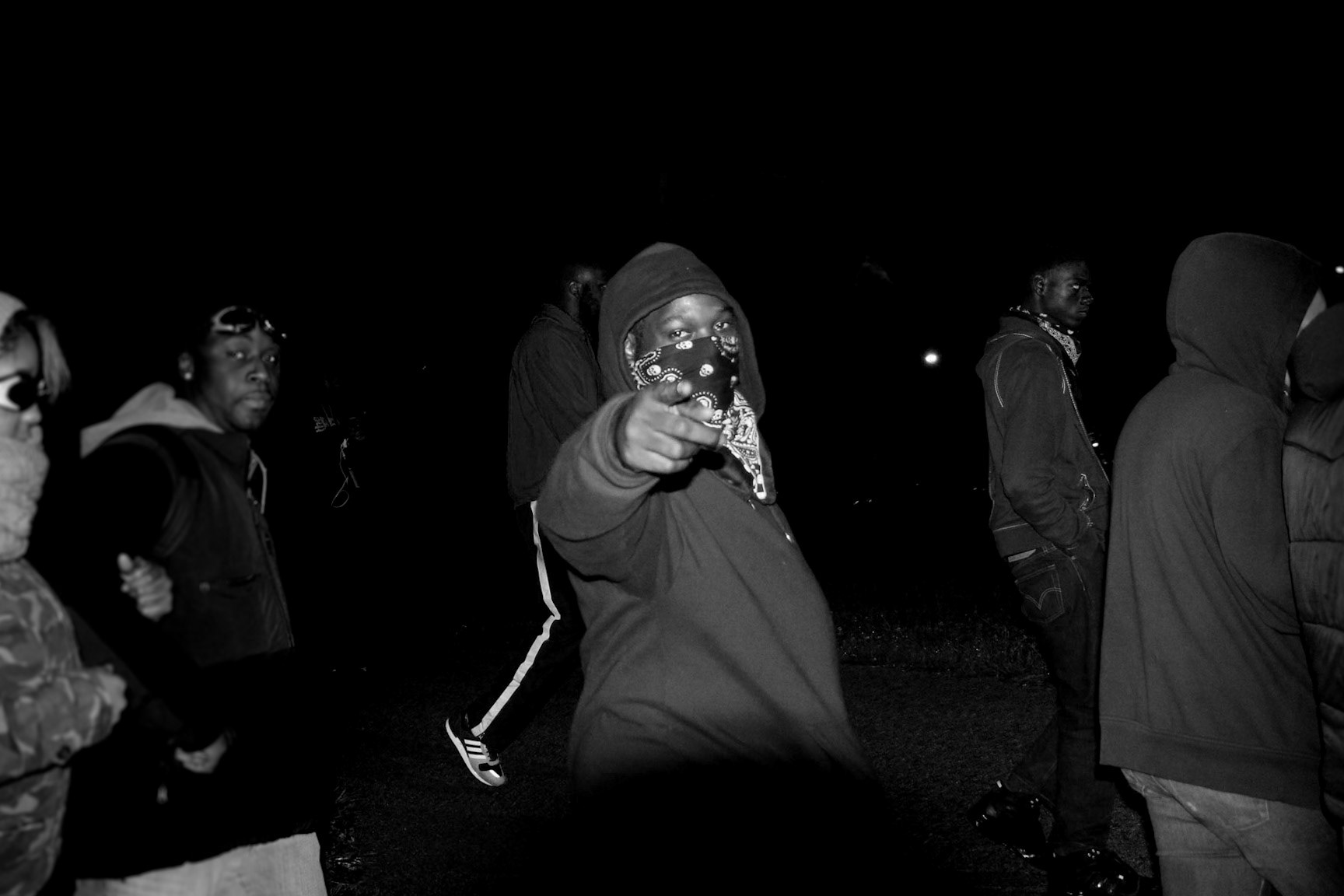

With cultural influencers under heightened scrutiny in the authoritarian “new Turkey”, Susamam’s artists had to choose their words wisely. Rappers have been jailed for lyrics that “promote criminality”, so to dodge censors, the MCs shirk partisan politics and instead, like Şanişer does, invite the listener to reflect inward: for each time you avoid eye contact with the homeless or, if you’re a man, fail to question if your status at the top of the pyramid is a privilege you really want to have. “In that jail scene, I’m criticising myself,” Şanişer says. “I’m a ‘white Turk’, we’re the people who had the chance to think and act, and we didn’t. That’s Susamam’s message.”

Its message is subversively crafted to transcend Turkey’s political battlegrounds. “If someone who doesn’t have the same political views as me listens to one part about the traffic problems, or animal rights, and agrees with it, he’s also listening to something he wouldn’t normally hear,” Şanişer says. “And that’s the first way to change people, by making them listen to another person’s side of the story.” In a divisive time, perhaps it’s the approach that’s needed.

As a major pop culture and commercial force, rap is relatively young in Turkey, and it is still music many parents would forbid their children to listen to. Grounded more in the tradition of spoken word and poetry of the Middle East and Asia than western hip-hop culture, Turkish rap has its own rhythmic grammar. The language’s jumbling syllables demand a lyricist chop bars more like a syncopating freestyler, than depend on the beat to carry their verse.

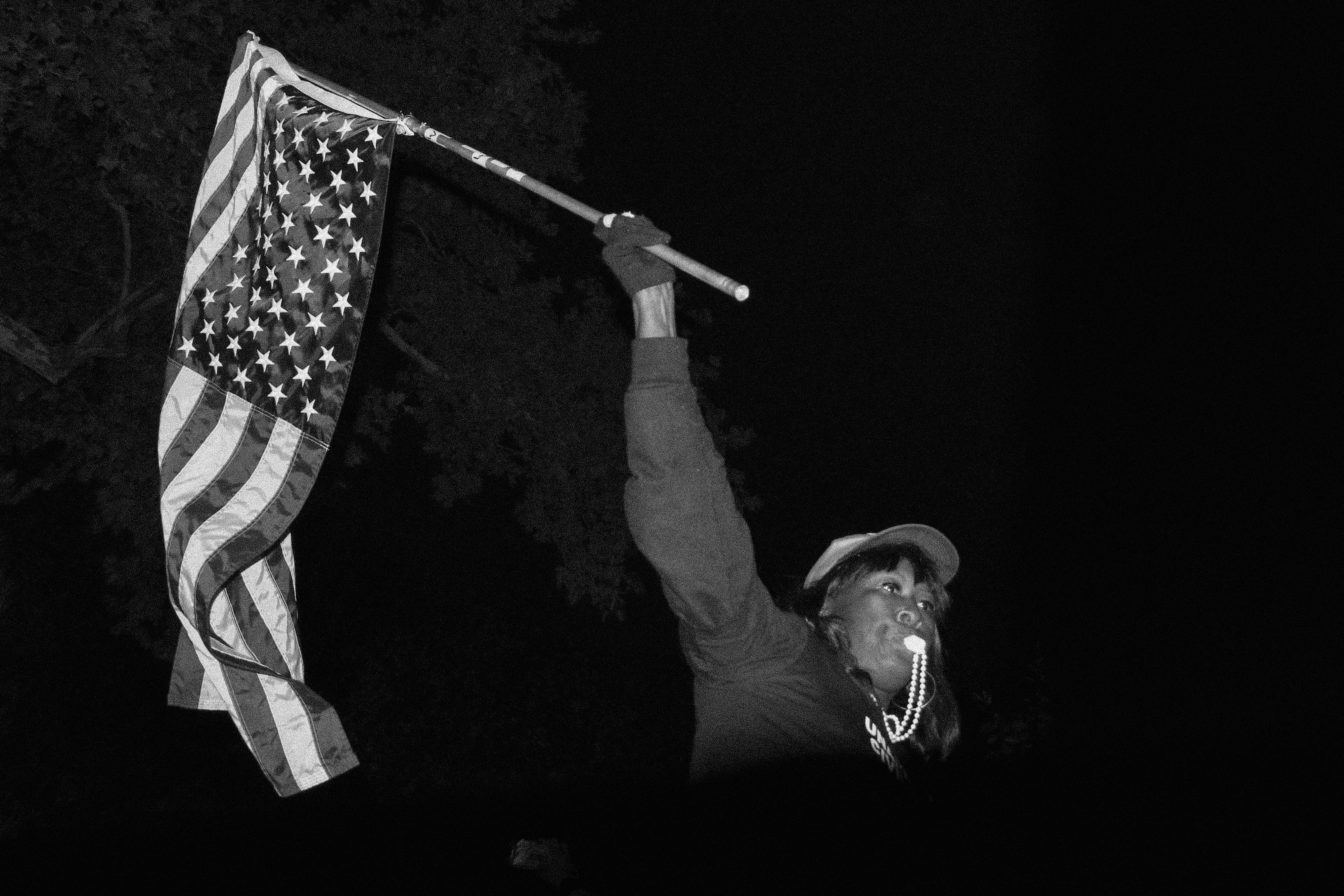

With few paths for artists to sign big-break record deals, the genre remains underground, making rap shows one of the few remaining free outlets of Turkish political consciousness. The typical attendees are young men coming after long work shifts, unable to understand the English lyrics of western rap, or relate to the high-flying materialist culture it comes from. Civil war, pogroms and jingoism are all in the Middle East’s recent past – so empty materialism doesn’t impress crowds. “Music is an art, but anything that makes money gets corrupted,” Şanişer says. “I used to think that rappers were all against the system, against the inequality it creates, but I realised that many of them were just poor.”

Turkey has always struggled to have a single identity, despite nationalist politicians pushing the idea. A new generation, fed up with the patrimonial past, want to create something homegrown they can be proud of, and finding it in lyrics such as: “Hate is your weapon … Our weapon is our words!”

Full of juxtapositions and familiar references, Susamam goes on (and on), at times veering to the saccharine tone of a We Are the World reboot. One section reflects on traffic accidents, which kill 10,000 people in Turkey every year; a section on suicide pulls at heartstrings, while another on education sets alight the lie of meritocracy (the chief of Turkey’s Central Bank was condemned for plagiarising his masters dissertation, but is still in office).

Susamam, whose film has the option of English subtitles, also takes aim at issues that are as global as they are specific to Turkey. “We’ve lost our conscience as a species – we’ve become programmed, obsessed with chasing growth and profit,” Şanişer says. “The root cause of these problems is wild capitalism, and this is a problem not just affecting Turkey.”

The chapter on women’s rights stands out for its raw gravity. Taking a break from rap, it features the only female vocalist, Deniz Tekin (although Turkey does have female MCs) singing a sardonic ballad, pretending to be oblivious to the daily curse of being a woman in a violently patriarchal world, cut with real video and audio clips of violence against women.

“This is a huge problem in Turkish culture,” explains Fuat Ergin, the first artist on Susamam, and one of the originators of the Turkish rap scene back in the 80s. “You’ve got a guy who can’t deal with a divorce, so he kills his wife – they get a ‘discount’ on the prison sentence, and these guys get huge respect inside the jail, because he did something to redeem his honour. This is how people see things here.”

There’s a Turkish idiom that goes: “You’re a male, but not a man.” The section’s lyrics challenge that machismo mentality by flipping it to:“You’re a man but not a human.” Fuat says: “This is an arrow that we’re shooting through the heart of their honour culture.” The track continues: “Why are the males at the top of the pyramid, in the nation, at home, or in the metro?” – a reference to Istanbul’s Metrobus system, notoriously avoided by women for its unchecked sexual harassment.

Susamam takes its most abstract philosophical turns just when it comes to the most controversial items on the political agenda. Rapper Ozbi, the only Kurdish artist in the project, ruminates on his existence; in a country where Wikipedia has been banned for years, he asks: “Is understanding banned, too?” Speaking Kurdish was banned for decades, and though Kurds have gained significant cultural rights, they still face discrimination as second-class citizens.

Ozbi’s questioning is necessary for political action, and though the video was produced before Donald Trump pulled the US out of the region, reigniting fighting between Turks and Kurds, its message is relevant as ever. Susamam traces a path forward that, disastrously, is not being offered by Turkey’s political climate.

“The point of this song is that it’s possible to live together in peace and walk this way without killing each other, without the vendettas. It’s possible,” Fuat says. “It’s a very painful process to forget all the blood. Many families lost their sons and daughters, on both sides. This is taking Turkey down, but we have to get over it. We don’t want this war any more. This has to stop.”