The streets of Istanbul are transformed into something like a festival ahead of Turkey’s presidential and parliamentary elections on June 24. Just about every street in the metropolis of 20 million is draped in party flags, marking political leanings from one neighborhood to the next. In liberal districts, the multi-colored banners of the opposition parties stand out from the rest of the city. Everywhere, there are photos of the current president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Campaign trucks drive around with loudspeakers blaring his name: “REEE-JEEEP TAAAY-YIIIP EEER-DOOO-AN!”

In the midst of all this, down a side street in the affluent European district of Şişli, is a high security fence surrounded by barricades and guarded by armored police. It’s easily mistakable for a military base, but it houses Cumhuriyet, the last major independent newspaper in Turkey.

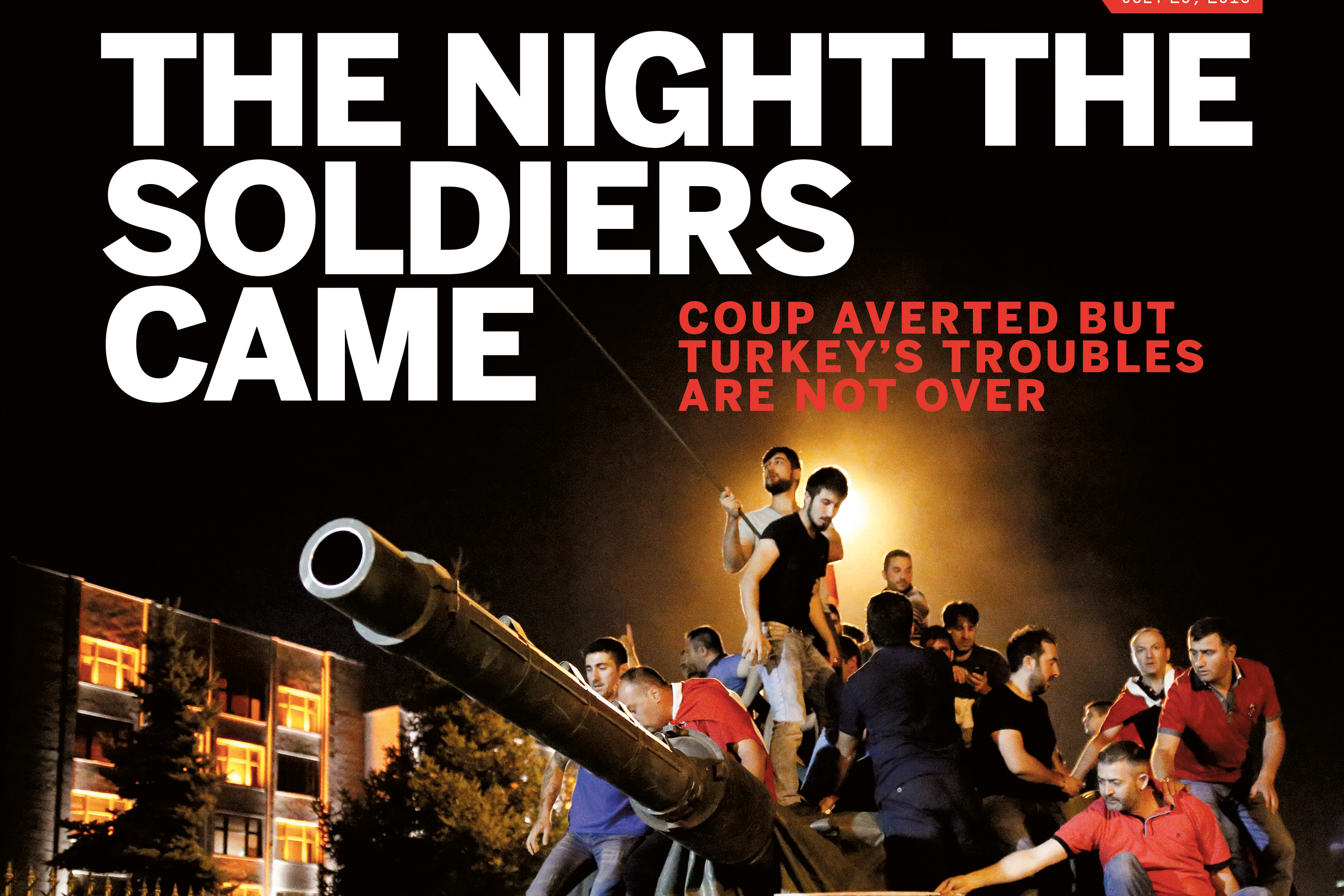

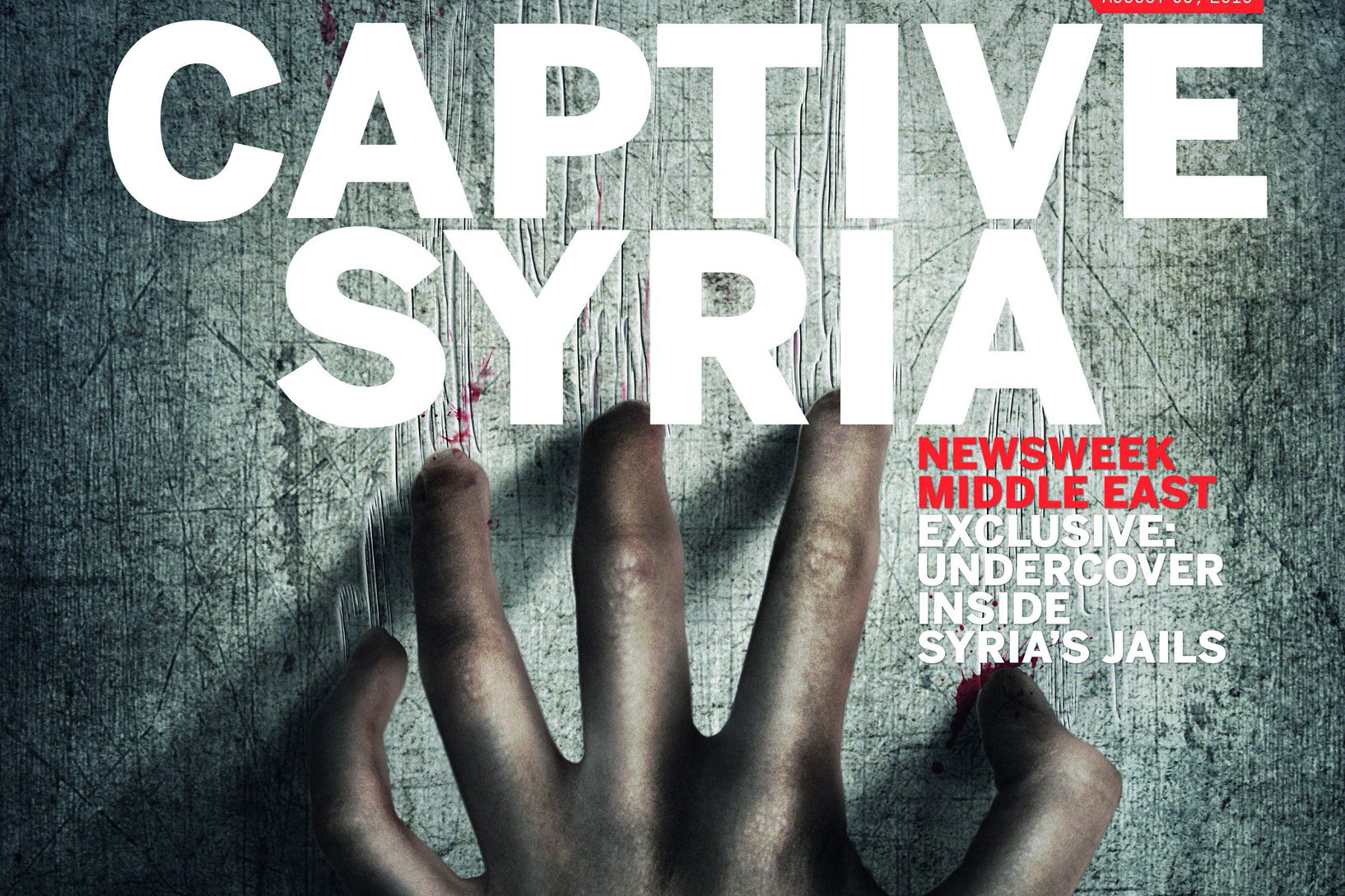

Cumhuriyet, whose name means “Republic,” is facing dark days. Its offices have been raided, its reporters imprisoned. Turkey currently imprisons more journalists than any other country in the world, and since the failed military coup in July 2016, one media outlet after another has been closed down, appointed government trustees, or been bought out by élites close to the ruling Justice and Development Party (known by its Turkish acronym, AKP). Yet Turkey’s paper of record continues to stand out as a rare critical voice in an increasingly authoritarian environment. Its commitment is to keep reporting the truth, no matter the cost.

Every morning, Murat Sabuncu, Cumhuriyet’s editor in chief and lifelong newsman, starts the meeting with an indelible smile and the eager energy of an intern. Along with 17 of his colleagues, Sabuncu was imprisoned for a year and a half on charges of publishing news articles publicizing the actions of three different terrorist groups. He was released in March, although only temporarily. While his case is being appealed to the European Court of Human Rights, he is working everyday at the newspaper in the run-up to the election. If the appeal fails, he faces another six years in prison.

“The principles Cumhuriyet was founded on are very clear: republican, secular, democratic, and pro-freedom of ideas,” Sabuncu says with confidence. “We are independent. Not just recently, it’s been this way since the beginning. We are the watchdog of this country—we are not afraid of anything.”

Images of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, founding father of the Turkish republic, are displayed prominently on the walls of the conference room. Beneath one portrait reads a quote: “What they see, what they think, what they know, journalists must write!” Atatürk is revered by many Turks, and his ideology, known as Kemalism, has long represented Turkey’s nationalism. Cumhuriyet was founded soon after the Turkish Republic, as the legend goes, on Atatürk’s orders. The values Cumhuriyet stands for haven’t changed, but the government has. Turkey was long a one-party state under the party of Atatürk, the Cumhuriyet Halk Parti (CHP), or People’s Republican Party. In the past decade and a half, however, the government has been dominated by Erdoğan’s AKP.

The CHP is placing their hopes in one of the opposition candidates, Muharrem İnce, for a win against Erdoğan on June 24. The election is a critical moment not only for Turkey, but for the paper. It consolidates newly expanded powers over the judiciary and government apparatus in the president’s office, which were passed by a referendum last year. The constitutional changes passed by a margin of 1 percent, amid allegations of voter fraud and ballot-stuffing. If things continue as they are, the paper could succumb to the pressures of a government whose tolerance of opposition has grown thin.

“As Turkish citizens, we’ll be watching our votes very carefully,” Sabuncu says. “And as journalists, we’ll be watching the polling stations on election day very very closely.”

In the week leading up to the election, its front-page headlines are unmistakably anti-government: “ONE MAN RULE”; “WHO IS LYING?”; “EMERGENCY RULE MAKES ALL A VICTIM”; and “ERDOĞAN IS A WHITE TURK”—implying that the Erdoğan has become one of the élites that he used to oppose.

Cumhuriyet has 246 reporters around the country, and correspondents embedded in each campaign. But covering the candidates isn’t always easy. Take Selahattin Demirtaş, with the pro-Kurdish HDP, who is running his campaign from a maximum-security prison. Sabuncu pulls up a recent documentary video report Cumhuriyet did with Demirtaş’ wife, who is speaking to her imprisoned husband over the phone. A generation ago, Sabuncu says, Cumhuriyet’s Kemalist audience wouldn’t have had a taste for such coverage of the long-marginalized Kurdish political parties.

At the 3pm meeting to determine tomorrow’s front-page stories, Sabuncu has made up his mind to go with İnce’s stump speech in Diyarbakır, in Turkey’s Kurdish-majority southeast. “This is something historic, the CHP is campaigning in Kurdish territory—and Kurds are actually excited about it!” Sabuncu exclaims.

If the newsroom staff is feeling pressure, it doesn’t show. Reporters diligently type away at their desks beneath a wall of TV screens, some playing election speeches, others showing World Cup matches. “Is anyone seeing reports of an explosion in Ankara?” someone calls out. “Confirmed fake,” responds Bulent Özdoğan, the editor on duty. “But we’re looking at reports of a stabbing at a campaign booth—two injuries,” the hospital says.” Özdoğan turns back to his computer with a sigh. “These kinds of things are all too common during an election.”

WHEN THE AKP FIRST CAME to power in 2004, says Berivan Aydın, a reporter on the foreign news desk, “they pooled all of their investment to buy their first media outlet, Sabah.” Since then, the AKP has used public-private investment partnerships to accrue a massive nexus of power that accounts for about 90 percent of print and broadcast media.

Earlier this year the country’s largest newspaper, Hürriyet, was bought out by a media giant that had already been taken over by a conglomerate with close ties to the ruling AKP. Many outlets that haven’t been shuttered by executive order are now under the control of government-appointed trustees. Those that are privately-owned are often pro-government. The Turkish government has also blocked websites such as Wikipedia, after discovering content it found objectionable.

There isn’t a single television channel operating today in Turkey that openly questions or criticizes the government—a fact which has major implications in election season. Few news reports amount to more than government press releases. When Erdoğan isn’t on screen, commentators are discussing his every word.

One channel, A-Haber, broadcasts patriotic songs and full-screen, windswept Turkish flags between news reports. When Turkey’s economy started to slide in 2016, Erdoğan called on Turks saying it was their “patriotic duty” to sell their foreign currency to bolster the rapidly-inflating Turkish Lira—and television stations broadcast the call on loop. In one commercial, a hypermasculine Ottoman soldier rides a horse to the top of a mountain, while the voice of Erdoğan dramatically narrates a heartfelt speech. The soldier stares out into the distance and brandishing a sword while a flaming phœnix rises—and the scene cuts to Erdoğan waving to a cheering crowd.

Cumhuriyet isn’t totally exempt from the AKP’s attempts at control, though the government hasn’t blocked Cumhuriyet’s website. “They’re smarter than that,” says Berivan Aydın, a reporter on the foreign news desk. “Instead they block individual articles on our website—they don’t even give us a notification.”

“Cumhuriyet is very careful about the sociopolitical redlines,” says Aydın. “Soldiers ’martyred by terrorists’ are always reported on the front page—yet the [pro-government] media claims that we don’t call terror by its name. We do, but regardless of whether the perpetrators are militants or officials,” Aydın explains. “It makes us feel like we are doing something right, to be on the side of truth.”

The paper’s tense relationship with the government ultimately affects its revenue. “We have high website traffic, and a really solid readership—but the private sector is afraid to buy ads from us,” Online Editor Bulent Mumay explains. Under different circumstances, he says, the paper could be pulling a lot more revenue from ad sales.

“Everyone is waiting for us to make a mistake,” Mumay says. “We don’t double-check, we check four times.” But, he adds, “There’s nothing we can’t do, so long as we have the proof.… Living in Erdoğan’s country, we try to do all the stories we can—we won’t stop because of censorship.”

Mumay, whose father used to work for Cumhuriyet, recalls the days when just carrying a newspaper was an act of bravery. “In the ‘80s, we had violence in the streets—left versus right, a military coup. When you were carrying Cumhuriyet in your pocket, you were proud of that, because it was a risk you took and you could get beaten up because you were carrying it,” he recalls. “It represented secular, modern life, the people who stood for human rights and democratic ideals. Now, in the Erdoğan era, it represents defending just a basic sense of democracy.”

Bulent Mumay, Online Editor carries the paper in his back pocket, as an homage to times long past, when reading Cumhuriyet marked you as a Leftist.If there is one thing that Cumhuriyet’s staff still feel they can rely on, it’s their readers, for many of whom the paper represents a strong sense of identity and pride. There are a few readers whose subscriptions are more than 50 years old, and they are known to stop by the building to complain to a columnist, or point out mistakes. Cumhuriyet staff keep and open-door policy, and consider it an obligation to take time out of their day to meet with readers in the lobby.

If it’s not a government order that stops the presses, the high-profile cases that jail journalists for terrorism charges, or the lack of advertising doesn’t run the paper out of business, it could be the legal fees that kill it.

Turkey’s defamation laws criminalize public insult, and courts can award compensation for claims, explains Abbas Yalçın, who has worked in Cumhuriyet’s legal department for nine years. Facing such lawsuits was always an occupational hazard for investigative newspapers, but these cases have intensified since 2016, when the ruling party was able to seize nearly all of the posts in the judiciary. At times, staff members could not be paid their salaries, but kept on working anyway.

“We used to win 95 percent of these cases; now we lose at least 70 percent,” Yalçın says. Asked how many court cases the paper has against it, he has to take out two tablet-sized ledger books and count by hand. After a long pause, he reports back: “At least 200 cases—that’s just since 2014.”

Each case that they lose comes with at least a ₺100,000 judgment (approximately $21,000)– and much more if the charges are criminal. Under the AKP government, Turkey’s courts have employed a broad interpretation of the counter-terrorism law. Prosecutors have argued that because the media publicize the actions of terrorist groups, journalists may be charged with “providing aid to terrorist groups without being a member.”

“It doesn’t help if we get our sources right and facts checked—it’s simply because we reported it—nothing more. In fact they don’t say anything about the content, or even try to say it’s fake,” Yalçın explains.

Most of the defamation cases aren’t brought from the government, but from private corporations on which Cumhuriyet journalists have reported. Mehmet Kızmaz was sued after he went undercover to report on worker injuries and deaths on the construction site of Istanbul’s third airport—a capstone government project. Çiğdem Toker, a star investigative reporter in Cumhuriyet’s Ankara bureau, has been sued by hospitals, mining companies, and the health ministry.

“These people didn’t sign up to be revolutionaries, they just want to do their job with dignity like anybody else. It’s their duty to report on corruption, and when you just pick up the phone and ask—You’ve received a public contract to do this construction, but where is the result?—you get sued,” says Aydın.

“Well, it’s a regime, after all,” she adds, wearily.

WITH 61 YEARS OF EXPERIENCE in journalism, Orhan Erinç is the longest-serving staff member at Cumhuriyet. For the past eight years, he has served as the paper’s publisher and head of the board of directors. He’s seen a lot of turmoil in his day—which he chalks up less to politics than to the country’s soul.

“Turkey has lost the logic of journalism,” Erinç tells us in his sun-drenched, book-filled office. “Businessmen owning the media is not something new—what was different then is that when a boss would try to dictate the news, a journalist used to say, You can’t buy me.”

He’s pessimistic about the future of the country. “Unions used to be strong in Turkey—but the AKP destroyed that,” Erinç says. “Now the media owners are ones who own the banks who are giving credit to farmers. Do you think they will report that the farmers can’t afford to pay back their loans?” The solution, Erinç suggests, is in education. “When you turn on the television, you don’t see a proper election happening—what does this say to the next generation of journalists?” he asks.

Ece Piroğlu, the youngest reporter at the paper, agrees. She graduated with a degree in journalism just this year and began at Cumhuriyet as an intern. She says that the education most Turkish students receive has nothing to do with journalism, and a final-year exam might be filled with questions like how many issues the main newspapers print, or what is the standard magazine page size.

“Our education is more about memorization than reading, writing, investigating, criticizing, and having an opinion,” says Piroğlu.

One of the young reporter’s assignments during election week is to go out and cover a CHP rally organized by an advocacy organization for children with disabilities. Accompanying her is Şenay Çalışgan, one Cumhuriyet’s accountants going on 32 years. Although she isn’t a journalist, she considers everyone working at Cumhuriyet to be family. Her father brought her into the newsroom when she was a teenager. “He told me I had to learn to stand on my feet,” Çalışgan says.

But for Çalışgan, there’s a more important reason to stay at Cumhuriyet. Her son is autistic, and she organizes with other parents to raise awareness about the issue—including lobbying the paper she works at to make sure they cover events like this one. She and other parents say that the government isn’t providing enough services for children who have special needs.

“A free press is not just for journalists’ sake,” says Çalışgan. “If there is no media to cover the government’s failings, then social issues like this go unnoticed and there isn’t awareness. Then, as a society, we’re dead.”