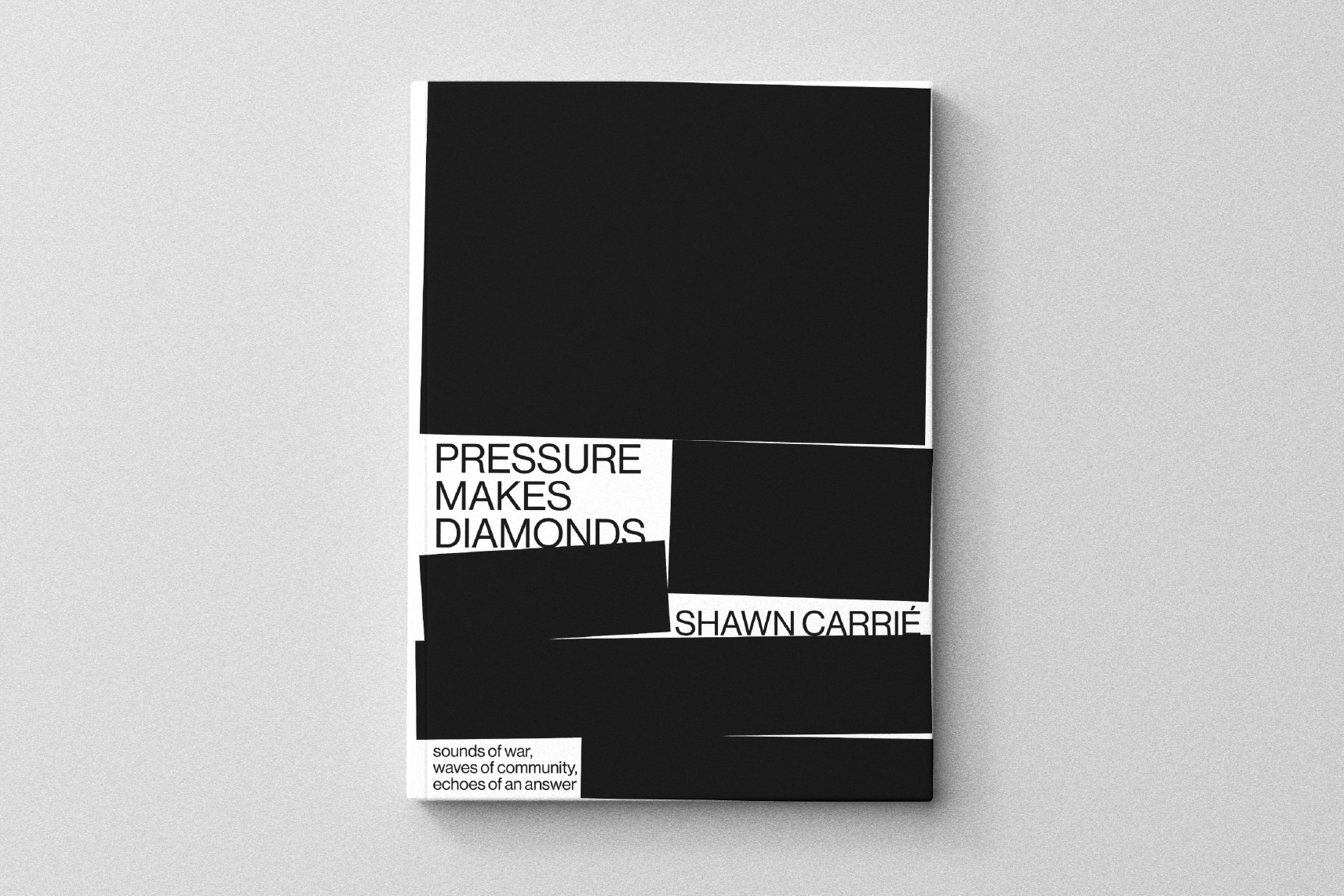

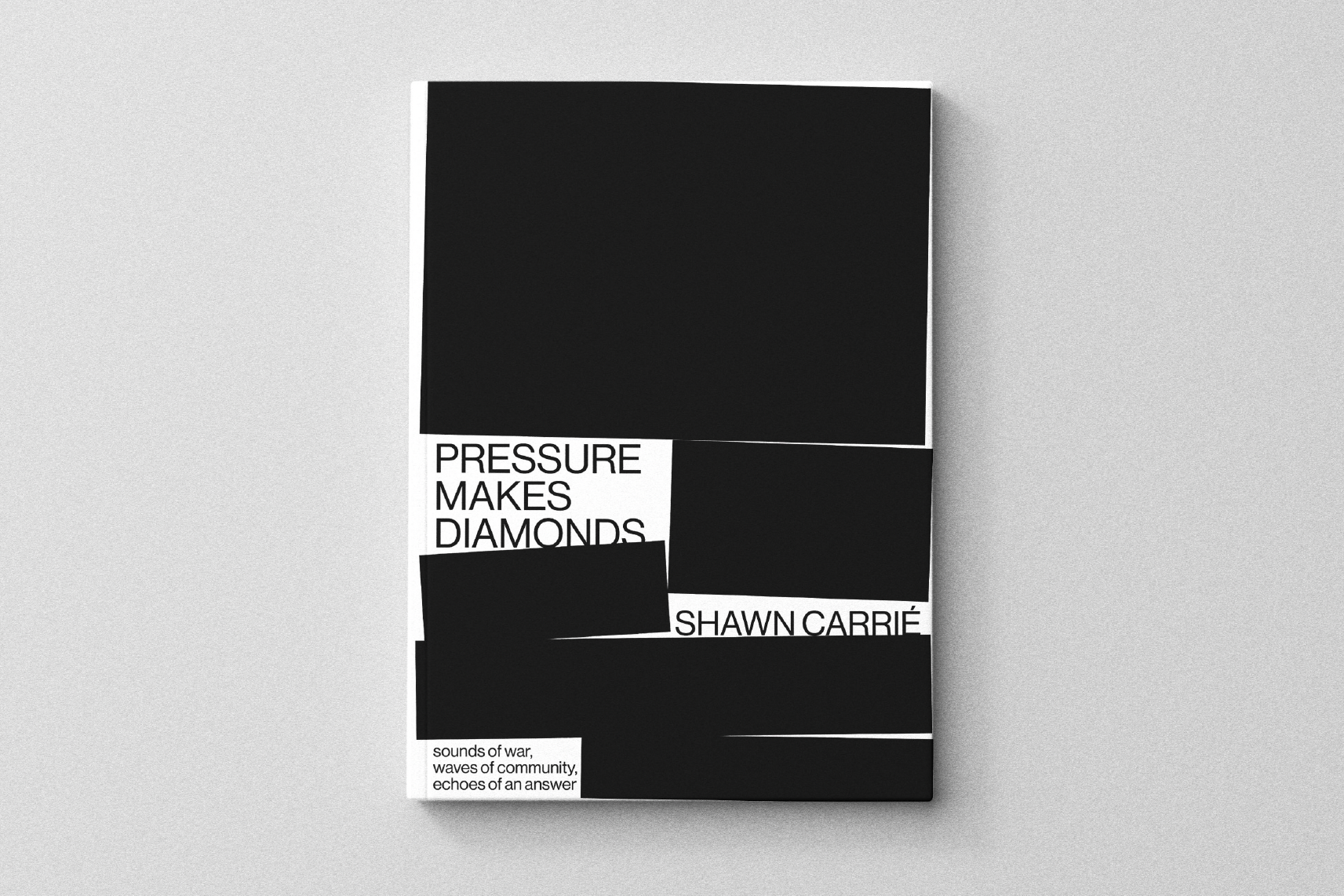

Cinemtography, translation, and montage by Shawn Carrié / Produced by Asmaa al-Omar

When 14-year-old Bakri first came to Turkey from Aleppo, Syria, the first thing he learned was how to live on the street.

Bakri grew up in Aleppo and lived with his uncles after his mother got cancer. In 2016, an airstrike killed the one uncle most like a father figure to him. The monthslong siege destroyed the city and forced residents to flee during a harsh winter.

Bakri arrived at the Turkish border town of Gaziantep when he was 12 and stayed with distant uncles, who sent him out to the streets to collect plastic and cardboard to recycle. He earned just pennies a day.

“I hated my uncles. They’d send me to work, and sometimes I would refuse and stay out on the street,” Bakri said. “[Once,] I was out playing with my friends instead of going to work, so they hung me from my leg to the ceiling and hit me with a pipe.”

Bakri’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

Elaph Yassin, who founded an orphanage that cares for Syrian children, recalls the first time she met Bakri at the Gaziantep bus station.

“I asked him what he needed money for, and he said, ‘I’m going to Aleppo to become a suicide bomber and take revenge,’” Yassin said. “When I asked him against who, he answered, ‘I don't care — against anyone. They took my family, so I want revenge.’”

As the Syrian war winds down and militant groups like ISIS lose territory and power, what remains is a “lost generation” that struggles to recover from the visible and hidden scars left by nine years of conflict and exile.

Children make up a third of the nearly 4 million Syrian refugees in Turkey. According to UNICEF, almost 400,000 Syrian children in Turkey are not enrolled in school.

“Out-of-school children are one of the most vulnerable groups in Turkey, and face multiple child protection risks, including psychosocial distress, child labor, child marriage and other forms of exploitation and abuse,” said Philippe Duamelle, UNICEF’s representative to Turkey.

From the streets to a ‘home with dignity’

Bakri is one of the lucky ones. He now lives at Karim Home, an orphanage on the outskirts of Gaziantep, where Yassin is a mother figure to around 60 Syrian children. Colorful murals drawn by children line the walls of the playrooms. Yassin’s mission was to create a “home with dignity” for abandoned, and abused, Syrian children.

Yassin and the caretakers live on-site, and daily life is organized around group activities and talking circles. Children attend a local school and when they come home, they attend daily counseling sessions to address complex traumas. They openly talk about abuse, exploitation and drugs — all things they often encountered while living on the streets.

“I don’t sugarcoat things. They have to talk about their traumas so that they know it’s not normal what happened to them, and that they’re not alone,” Yassin said. “They have faced traumas no person should have to face, and the world is going to continue being cruel to Syrians.”

Yassin, originally from Raqqa, Syria, invested her personal savings to open the orphanage in 2015. She earned a certificate in counseling to try to heal some of the scars — both visible and hidden — that the war has left on her country. Exiled from her homeland and unable to return, Yassin herself understands the trauma of war.

“No one can say that Syrians are not strong — these kids are stronger than any of us can imagine.”

Elaph Yassin, orphanage founder

“No one can say that Syrians are not strong — these kids are stronger than any of us can imagine,” Yassin said.

Sana, an 11-year-old resident of Karim Home originally from Qamishli, in northeastern Syria, has a shy smile and a tough demeanor beyond her years. Sana’s name has been changed to protect her identity. She says her mother was a sex worker, and she and her brother lived in the home of her mother’s pimp who sexually abused them both on a regular basis. She called the police to report him twice, but they sent her back home. On the third call, the police connected her with Yassin, who brought her to Karim Home at the age of 8.

“When I came here, I was sick. The other girls could tell by the way I walk that I was sexually harassed,” Sana said. She speaks with lucidity about the years it took her to get over the shame and struggle of leaving her abusive home. “But [here] they taught me that what happened to me was wrong, and I hope all kids know that,” Sana said.

In many Turkish cities, it’s common to see children — Syrian, Turkish, Kurdish or Roma — roaming the streets alone selling tissues or flowers. Aisha, 11, comes from Aleppo and lives with an aunt and uncle in the outskirts of Istanbul. She takes the bus into the city center to collect money with her five siblings and speaks enough Turkish to sweet-talk tourists sitting in cafés.“All of us have to come home with 50 liras,” Aisha said — a combined total of $60 among all six siblings. “When I don’t, I go to sleep without eating any dinner as punishment.”

A 2012 report by the Turkish Ministry of Family, Labor and Social Services found that child labor is an ongoing problem that affects 1 out of 17 children over the age of 6. “Children working away from family supervision and protection have their safety compromised, leaving them exposed to all kinds of exploitation,” the report says.

And places like Karim Home are few and far between. Refugees have little access to mental health and guidance, and even for those who do manage to get enrolled in school, the education system itself struggles to cope with the trauma that young Syrians carry into the classroom.

A school is not a home

Loubna al-Hamad works at a public middle school in suburban Istanbul and has seen many Syrian children pass in and out of the system. She says discrimination and bullying are common experiences for Syrian students who struggle to keep up with learning the language and integrating with Turkish classmates.

Official Turkish policies protect the rights of refugee children to equal educational and opportunities, but it rarely plays out in practice, with limited specialized support for Syrian child survivors of war.

“There should be psychologists in schools to help Syrians students deal their situation. There are none,” Hamad said.

Each public school in Turkey typically has a counselor on staff available to all students, Turkish or Syrian. But when it comes to specialized psychologists who focus on trauma, teachers must rely on generalized counseling referrals — which means that the child must leave school to see the counselor.

“First, they miss a few days, then they stop coming altogether and have difficulty continuing,” Hamad said.

In 2016, Turkey began the process of integrating refugee students from temporary education centers into Turkish-language classrooms. But when parents and caregivers can’t speak Turkish at home to help with homework or meet with teachers, the difficulties add up, making truancy likelier.

“There are many issues that can prevent a child from attending school. If they don’t have the right ID card, or don’t have residency, their transcripts from previous years, they can be de-enrolled and schools don’t accept them anymore,” Hamad said.

A temporary asylum protection law affords Syrian refugees free access to health care, schools and social services, but they can’t access those services without ID cards. Only 3% of college-age Syrians in Turkey go on to higher education and less than 1% have been issued legal work permits.

Despite the public denial, Turkish officials quietly admit that refugees continue to be denied registration by provincial authorities, rendering them undocumented and excluded from services.

A joint curriculum for psychosocial support programs written in 2001 by UNICEF and the Turkish Ministry of Education wasn’t updated to account for the refugee influx until the 2018-2019 school year. In the year before, existing programs that referred students from schools to community-based psychologists only reached 8% of refugee children.

“Specialized services by mental health clinicians and social service professional [for Syrian students] remain insufficient to cover all needs,” said UNICEF spokesperson Philippe Duamelle.

Resentment or acceptance

The Turkish government has welcomed nearly 3.5 million Syrians, but years of dissatisfaction among the Turkish people have led to discrimination and xenophobia. In upcoming municipal elections, Turkey’s fastest-growing opposition party, the Good Party, is running on the slogan, “We won’t deliver our cities to Syrians,” promising to send them back to Syria, even though UN officials maintain conditions are unsafe for return.

With a dearth of government services, caring for Syria’s most vulnerable children and youth in Turkey is left to nongovernmental agencies and private charities like Karim Home. The orphanage is wholly funded by private donors in the Syrian community and rejects funding that “comes with strings attached,” Yassin said.

“I used to be filled with anger; this place helped me a lot, in every way. I forgot the harassment and feel like I can face my uncles and everyone who treated me with injustice.”

“I used to be filled with anger; this place helped me a lot, in every way,” Bakri said. He has come a long way toward healing. “I forgot the harassment and feel like I can face my uncles and everyone who treated me with injustice,” he said.

But Yassin fears that a generation of Syrian children has been left vulnerable to those who take advantage of their suffering, including extremists and radical groups.

Bakri recalls his days back in Aleppo when he used to encountered street gangs who did business with militants. Years ago, a group of men offered him and his friends cellphones and money to drive a car to a nearby rebel group’s checkpoint down the road.

“I said, ‘I’m only 9, and I don’t know how to drive a car,’ but he said, "It’s easy,"" Bakri said.

Later that day, they heard that a car bomb had exploded just outside the town. “I knew that they had gotten someone else to do it for them, and I just thanked God that it wasn’t me in that car,” Bakri said.

“This is the story of the Syrian community — it’s a cycle of violence,” Yassin said. “What can I do to erase all this pain? They are crying, there’s nothing to do, but cry with them.”