Shot, edited and translated by Shawn Carrié, produced by Pesha Magid.

We hear Ahmed Abdulrahman before we see him. He is preceded by the sounds of hammers clacking and concrete being moved around. We make our way from the street, through a narrow entryway scattered with bits of broken stones, shattered glass, and wiring. The entrance is damaged and its walls lean precariously. A sheen of white dust covers every surface. We emerge into an inner courtyard, where Abdulrahman is working cheerfully in a knitted blue and grey sweater that wouldn’t look out of place on a Norwegian grandfather. Goggles perched atop his head, he is a beaming, bearded steampunk repair man.

<--->

He lives in the Old City of Mosul. Most houses are mutilated, empty frames, but the neighborhood bears the signs of life. With a small toolbox in hand, he goes from house to house, cheerfully greeting people, helping them with small repairs, finding work or medicine. If there is a problem in the neighborhood, Abdulrahman is the first person to turn to.

“If you get someone who’s relaxed and not under pressure, then they’re fine,” Abdulrahman says, “but someone who’s been living for a long time in a destroyed place like this, he’s like ‘aaaaah’!” Abdulrahman throws his hands in the air with the growl of a monster in a children’s story. “Then they always make trouble, yes indeed,” he concludes, with a matter-of-fact grin. Locals elected Abdulrahman as a sort of neighborhood mayor and multipurpose problem solver — otherwise known as a mokhtar.

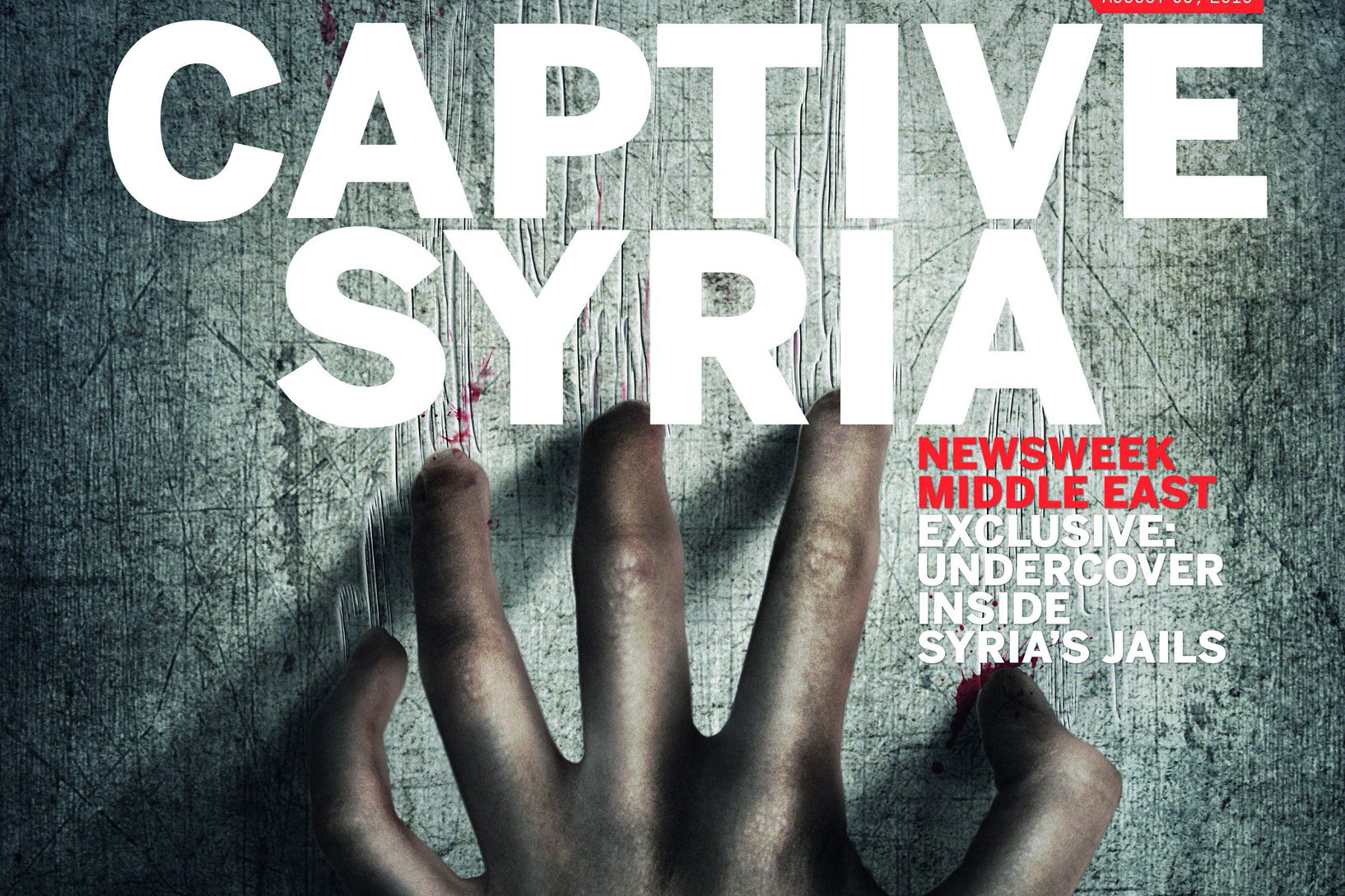

The streets of the neighborhood resemble a bizarre, space-like desert of pulverized stone and bomb-twisted metal. It was here, in the Old City of Mosul, that the final battle to remove the Islamic State, also known as Daesh, reached a violent crescendo last year. The neighborhood is home to the famous al-Nuri mosque, with its iconic hunchback minaret, where Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the Islamic State leader, proclaimed a caliphate in Mosul. As Iraqi forces closed in and defeat became imminent, the Islamic State rigged the 850-year-old mosque with explosives and blew it up, just to rob them of a symbolic victory.

Today, the sprawling grounds of the al-Nuri mosque are a scrap metal yard. Rusty cars are piled on top of each other. Men push around carts collecting parts that can be recycled. It’s the only area where any rubble has been removed, even if only to make space for a junkyard. In the surrounding neighborhood, the destruction spreads out, spanning block after block.

Standing in the midst of a shattered home, Abdulrahman is blunt: “All of this destruction wasn’t made by Daesh.”

The Old City of Mosul survived the American invasion of 2003, the bloody decade of insurgency and civil war that followed, and three years under the Islamic State’s caliphate. The nine-month battle to wrest the city from the Islamic State occupation, led by U.S.-backed Iraqi forces, killed thousands of civilians. It extinguished entire families in seconds. Across Iraq, it displaced millions to refugee camps, many of them from Mosul. It erased years of the city’s history, its dignified 18th-century facades, and the beating heart of the city where both trade and tourism had thrived. It did more damage to Mosul in those nine months than had occurred in the previous 14 years.

Today, people speak about the Old City’s residents with hushed tones of pity: Many of them saw their entire livelihoods vanish in one day, often at the same time they lost family or friends. No other part of the city was damaged as badly. Yet in the Old City, state-led rebuilding efforts are almost nonexistent. No one knows how long it will take to make the Old City livable again — most estimates say it will take years.

Mosul residents are left asking: Who will pay for the reconstruction? The answer isn’t clear, except for one part, which is that America will not be involved, even though its bombs were responsible for the lion’s share of destruction. Now that the caliphate has been toppled, there is no plan for what comes after.

<--->

Iraq estimates that it needs $88 billion to rebuild following the war against the Islamic State, and hoped to drum up funding from foreign donors at a major international donor conference in February. But Iraq only managed to raise pledges of $30 billion, much of which was for loans and investment rather than direct aid. While Turkey pledged $5 billion, and Kuwait and Saudi Arabia each pledged $1 billion in loans meant for rebuilding, the U.S. was conspicuously absent from the donors list. Instead of pledging any direct loans, the U.S. will pursue “development through a model of investment rather than aid,” then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said in a speech. His remarks were not happenstance. “Immediate stabilization needs remain vast, and limited U.S. government resources alone cannot meet these current and pressing needs, let alone consider supporting long-term reconstruction,” a spokesperson for the State Department told The Intercept.

American foreign policy — which amounts to pouring billions of dollars of military spending into Iraq, but little on economic aid or investment — is not a popular one. “I can’t tell you how hollow the Tillerson speech rang,” said Saad Aldouri, a research analyst at the London-based think tank Chatham House, who attended the Kuwait conference. “The main thing he stressed was helping the Iraqi government reach out to private business and helping American companies invest in Iraq.”

But even those promises from Tillerson have yet to materialize. At the conference, Tillerson cited two U.S. government agencies — the Export-Import Bank of the United States, or EXIM, and the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, or OPIC — as potential facilitators for investment. The Intercept contacted both agencies, and neither was able to confirm any upcoming projects in Iraq. EXIM is without enough board members to approve any new projects, while OPIC does not publicly list any new proposals at this time. Its past projects in Iraq include $21 million for the construction of a Hilton DoubleTree hotel in Erbil.

“I don’t want to say it’s nothing, but it’s nothing material, at least,” Aldouri said.

When the U.S. invaded Iraq 15 years ago, it dismantled the Iraqi state and installed an interim government which presided over a series of disastrous decisions that helped prompt enduring warfare, at first against the U.S. occupation, then between Iraq’s Sunnis and Shiites. It had catastrophic consequences for the country, and cost America over $2 trillion. In the aftermath, there is only a military strategy for Iraq, not an economic one.

“When you talk to U.S. officials, there is this continuous emphasis on the idea that ‘we helped you, now it’s time for you to help yourselves,’” explained Harith al-Qarawee, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council.

President Donald Trump hasn’t said much about Iraq since the fighting finished. He has, however, taken the time to make clear that he thinks the U.S. shouldn’t spend any more money in the Middle East — with the notable exception of the military. Trump’s 2019 budget requested $15.3 billion in funding to continue the anti-ISIS mission in Iraq and Syria — an 18 percent increase from the year before, and almost $4 billion more than the year that the Islamic State was defeated in Mosul.

“This is classic,” noted Aldouri. “The biggest fear and criticism is that this administration’s policy facing ISIS has only really valued a military dimension. There hasn’t been any inkling of post-conflict planning.”

< >

The topography of the city has been altered by the war. Nestled along the right bank of the Tigris, Mosul al-Qadimah was for a long time the busy, bustling heart of the city, filled with markets and prospering businesses. The formerly spare and professional districts of the left bank have been transformed into a new city center. As many have been displaced from the west side of the city, east Mosul appears alive with activity. Shops bustle with customers and restaurant tables are full.

Today, crossing the bridge into the Old City feels like entering another world. The transition is slow at first, then sudden. The checkpoints multiply and the streets grow emptier with every meter. The inner guts of the houses have been ripped open — the concrete and wires that make up the walls of homes point to the sky like strange fingers.

The Old City was singularly destroyed. Other neighborhoods on the west side bear the signs of the bombardment in broken buildings and heavy security, but they are also slowly returning to life. A few minutes away is an open-air market full of tradesmen plying their wares, which range from a signature crispy eggplant shawarma to fresh fish. (Mosul is famous for its red carp, normally grilled whole over an open flame.) The Old City looks dead in comparison.

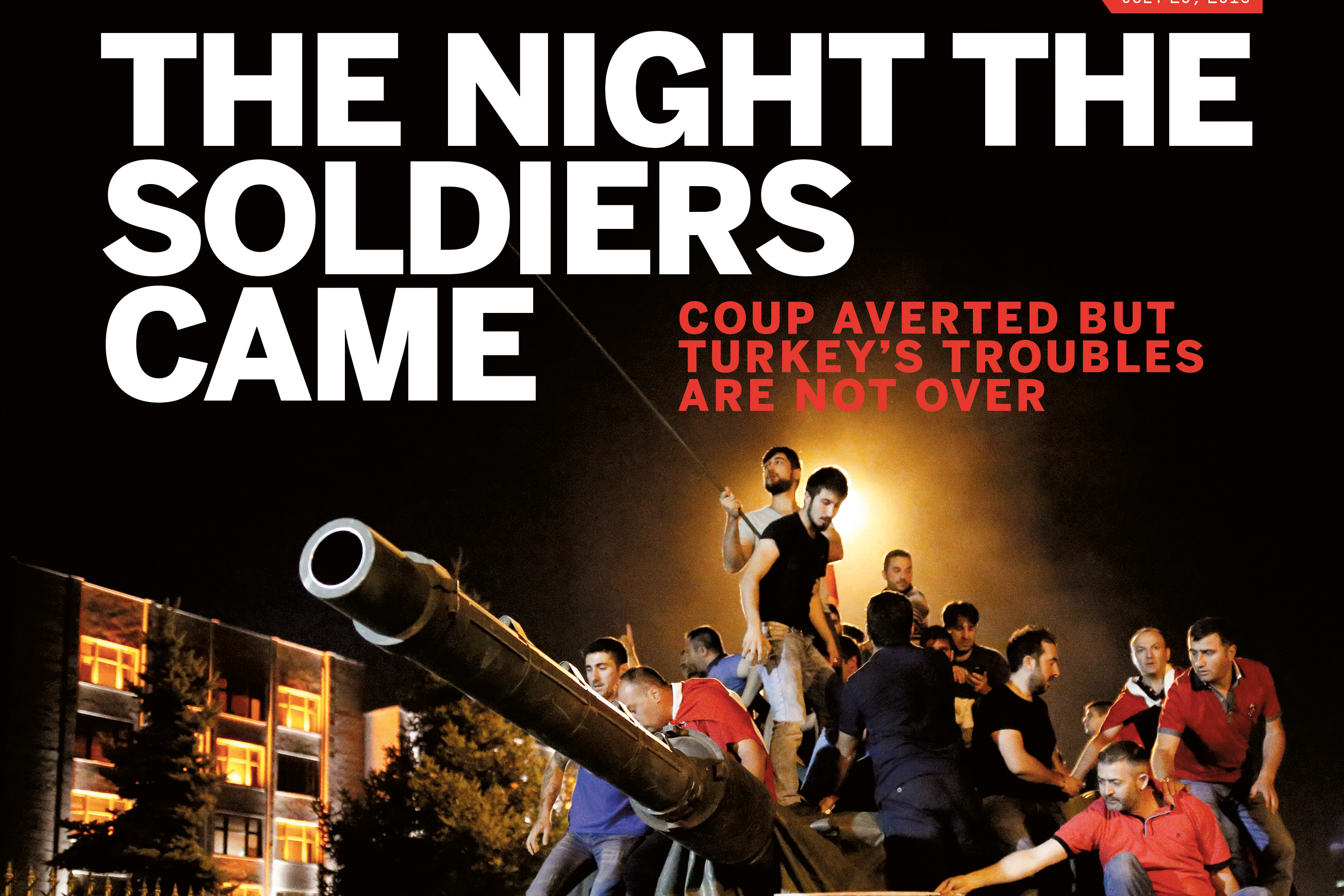

When the battle to take back Mosul was announced in October 2016, it only took three months for Iraqi security forces to retake the eastern half of the city. By late January, the Islamic State had been pushed to the west side, where the last remaining fighters dug in their heels. They blew up bridges as they went, isolating river bank neighborhoods like the Old City, fortifying densely packed areas, and fighting a close-quarters battle for each street. The civilians who lived there couldn’t leave; the Islamic State herded them from house to house as residential neighborhoods became the battleground. To escape the fighting, civilians had to make a run for it in the midst of the chaos. Those caught trying to flee to Iraqi troops — who were sometimes mere meters away — were treated as traitors to the caliphate and shot.

The Old City’s maze of narrow, winding streets were too difficult for maneuvering by armored forces from Iraq and its western allies (principally the U.S., but also Britain, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Australia). Death from the air became the Iraqi and U.S. weapon of choice.

Zahra Billah is 54 years old, but looks much older. She lives with her daughter, Ismaa, and her grandchildren on the same street she was born on. Her family members are the only people living on her street now. Her home, in stark contrast to all of the houses around it, is the only one standing. “The government wanted to destroy Daesh, but it is the people who paid for it with death — with our houses, with this destruction,” she said.

Infrastructure was one of the first casualties of the bombs. Billah’s house survived, but there is no system of infrastructure for it to connect to, which makes being poor expensive. It’s not that the essentials aren’t available — it’s just that everything costs money. It means carrying in bottled water for all their daily drinking, cooking, cleaning, and showering. Renting a portable gasoline generator for a few hours a day, to supply electricity, costs nearly as much as the rent. A small gas canister burner does all the cooking and heating.

Three generations of women live in this house. This is not the first war they have lived through. Billah remembers the nine years of kerosene heaters from the war with Iran back in the 1980s, the Persian Gulf War in 1990 and 1991, and of course the U.S. invasion in 2003. But, she says, none of them compared to the U.S.-Iraqi war against the Islamic State.

“I was born here and I grew up here and I have never seen anything like this,” she says. “They destroyed the neighborhood. The reason for all of this, I don’t know.”

AFTER VICTORY WAS DECLARED over the Islamic State, Defense Secretary James Mattis addressed the press triumphantly. “There has been no military in the world’s history that has paid more attention to limiting civilian casualties and the deaths of innocents on the battlefield than the coalition military,” Mattis said. “Precision gave us options that we never had before in history.”

It was a precision strike that caused the single greatest instance of civilian deaths in the course of the Mosul battle — possibly the largest incident since the American invasion in 2003. On March 17, coalition surveillance identified two Islamic State snipers on the roof of a three-story building in west Mosul’s al-Jadidah district. What they didn’t know at the time was that hundreds of civilians were sheltering inside the basement. An airstrike was called in, and a single 500-pound bomb was dropped by an American fighter jet. The strike leveled the building, and the one next door. Rescuers were unable to reach the area for days, and the damage was so catastrophic it took weeks to pull all the bodies from the rubble.

Under immense international pressure, the U.S.-led coalition admitted responsibility for the strike and paused its air campaign to conduct an investigation. The selected bomb was intended to kill only the two snipers on the roof. The U.S. report claimed that the strike then inadvertently triggered a stockpile of explosives placed in the building by Islamic State fighters, bringing the whole structure down on civilians hiding in the basement. Iraqi officials and locals in the al-Jadidah district disputed those findings, saying they found no evidence of explosives when they arrived at the site to remove the bodies.

When rescuers finally finished clearing the wreckage, 213 civilian bodies were pulled from the site of the strike, the head municipal engineer in charge of Mosul’s al-Jadidah sector, Doraid Hazzim, told The Intercept (the coalition acknowledges 105 civilians killed). Hazzim says the kind of error that occurred at al-Jadidah was far from exceptional. “This happened many times,” he said. “A Daesh fighter stands on a roof and shoots at the army, but the house would be full of civilians.”

The massacre at al-Jadidah was in March 2017, after which things only got worse. In May, Mattis stated that coalition forces had shifted to using “annihilation tactics” in Mosul. Shortly afterward, the battle reached its bloodiest heights. But an increase in civilian casualties can be linked to decisions that the U.S. had made months before.

A directive, made in December 2016 by the commander of coalition forces, Lt. Gen. Stephen Townsend, delegated bombing authority to American advisers embedded with Iraqi units, allowing more commanders in the field to call in airstrikes. Rather than waiting for “deliberate strikes,” which involve intelligence gathering and monitoring before authorizing an airstrike, the change allowed for “dynamic strikes” called in from the front lines. In the final stages of the battle, coalition authorities say over 90 percent of strikes fell under the dynamic category.

Officials argue that the December directive allowed commanders on the front lines to make quicker decisions in the midst of battle, and that while the coalition was dropping the bombs, it was Iraqi units leading the charge who were pointing out the targets. “We did delegate authority to lower level commanders, which increased safety – not decreased it,” Eric Pahon, a spokesperson for the Pentagon, told The Intercept.

This does not appear to be correct.

“There was a very close correlation between the intensity of the coalition and Iraqi bombardment, and the number of civilians being killed or injured,” explained Chris Woods of AirWars, an independent monitor that tracks airstrikes in Iraq and Syria. “Now, that sounds obvious, but actually the raw data said the more bombs and missiles you drop, the more civilians you’re going to kill — that’s exactly what happened.”

After surveying city morgues and gravesites, the Associated Press estimates that between 9,000 and 11,000 civilians were killed in Mosul, and that coalition or Iraqi forces were responsible for at least 3,200 of those deaths. But that’s just an estimate — in the chaos of war, it’s hard to be sure who killed whom. A groundbreaking investigation by the New York Times was the first and only systematic study of civilian casualties by coalition airstrikes. The Times visited the sites of more than 100 airstrikes throughout Iraq, and used satellite imagery and information shared by the coalition to get a representative sample that included both when strikes hit their intended targets, and when they didn’t. The investigation found that one in five coalition strikes killed civilians – more than 31 times higher than the coalition’s self-conducted reporting.

“The narrative of the coalition’s war is ‘we’re better than Russia because we use precision bombs, and therefore we don’t kill as many civilians,'” said Woods. “What we think has been clearly demonstrated is that any benefits of so-called precision warfare really have run up against the numbers.”

<--->

The woman in the pink hijab is angry. She screams, asking why the journalists haven’t come to look at her house.

She takes us down a small street cramped by hanging metal, expertly navigating the pocked ground and surrounding rubble to a small doorway. Through it is a mountain of rocks surrounded by four walls. The roof and a second floor are shattered into small chunks. What is left of her living room is open to the clear blue sky. Um Zaman climbs to the top of one of the hills of concrete to point out the extent of the damage. The mound is high enough to see over what’s left of the wall adjoining the building next door. All that remains of the neighboring house is a single sunken, azure-tiled peak of an arched doorway, a bygone world floating above the ruins.

“This is my house. This is the room where my son died, along with his wife. They were sleeping,” Zaman said.

Zaman is one of the people who paid the highest price for airstrikes. She stayed in her house in the Old City throughout Islamic State rule, until the airstrike hit. In the remains of a bedroom in what’s left of her house is a white sheet held down by broken pieces of stone. Under it, Zaman says, lie the bodies of her neighbors, buried in shallow graves among the debris. “The planes came and killed them as they were sleeping,” she repeated, still incredulous. “He had a son and a daughter who were with him, they all died. People from the neighborhood buried him. They did not even have a shroud. … They came back to cover them with blankets.”

Zaman cannot live in her house anymore. It is too broken; she only comes back to try and find some of her possessions among the ruins. She stands amid the mausoleum, as furious as if the airstrike were yesterday. There were only two Islamic State fighters on the roof when the warplanes came, she insists.

Parsing out just which party to the fighting is responsible for particular damage is difficult. Not least because there were so many explosions, it’s hard to tell who caused what. In areas where airstrikes were more isolated, it’s possible to compare reports from the field with satellite data and surveillance that the coalition conducted before a deliberate strike. In the Old City, where almost every building was destroyed, determining responsibility for individual airstrikes is all but impossible. The Islamic State used powerful car bombs against encroaching forces, so those forces responded with airstrikes. The month of June 2017 saw the coalition drop 4,100 bombs – one every 10 1/2 minutes.

It’s been nine months since the fighting ended. Hazzim, the head engineer in the al-Jadidah district, does not believe that the threat from ISIS merited such a destructive response. “They definitely bombed more than was necessary,” he said. “They could surround the city and stop letting food come in. It takes time, but they would not use bombs. There could be another way.”

A gaggle of children outside of Um Zaman’s home casually point out the homes where dead bodies of ISIS fighters are still left behind. People can give directions to dead bodies the same way that in other neighborhoods, they would give directions to the nearest pharmacy. Nine months after the fighting finished, some bodies still lie on top of the ground, rotting and making the air toxic to breathe.

A few blocks away, at Mar Thoma Church, an Iraqi soldier gives us a grisly tour of bodies that remain uncleared. The first body is just behind the gate. The skin on his face has turned black and shriveled with time. He was an ISIS fighter, the soldier, Rihab Naib, tells us. If it was not for his eerily undecayed beard and teeth, it would be hard to recognize him as human. Deeper in the church’s courtyard, one of the bodies has two cigarettes stabbed out in its eye sockets. “The soldiers did that and took selfies,” Naib says matter-of-factly, and keeps walking.

Leaving the church, our sentry hears a noise at the end of the street — his hand goes to the gun at his hip and we hear the staccato sound of the safety unlocking. An old man pushing a shopping cart emerges from around the corner, and the soldier relaxes. “Don’t be scared,” he smiles.

Satisfied at having protected the journalists, Naib settles into the checkpoint where he is stationed near the Old City’s two Christian churches. He is a member of the Popular Mobilization Forces, a militia of Shiite volunteers that was assembled in 2014 to support the Iraqi army in retaking Mosul. The PMF has now settled into a security role that has far outlasted the offensive. A few meters up the street is another checkpoint, and past that is another. Many of these checkpoints are quasi-official, little more than a teenager sitting on a reclining armchair with a Kalashnikov resting on his knees, or a few men standing around smoking cigarettes, drinking tea, and stopping people as they pass.

Naib says it is the responsibility of the local municipality to remove the bodies. Hizzam, who works for the municipality, says it’s the armed forces’ job to clear the corpses of those killed in battle. Hizzam only has 13 people working with him, and they do not have enough basic equipment like body bags, gloves, and masks.

The federal government has not disbursed any money at all to Mosul for reconstruction, and a budget crisis means that many municipal employees haven’t been paid their salaries in months. “They have given zero,” Hazzim told The Intercept. “Until now, there has only been promises, nothing more than that,” he added. “We work out of hope for the future.”

Hazzim says that they have removed 2,685 civilian bodies and 690 bodies of ISIS fighters since July. When asked why so many bodies were still out in the open, his first response was, “Are they Daesh?”

Behind the trading of blame is an unspoken element — there is a special disgust reserved for the Islamic State that extends beyond just the fighters, to the homes and even whole neighborhoods they occupied. Houses that once belonged to the Islamic State are marked with the word “Daesh,” spray painted in large letters. The bodies were at first left behind as an insult — but as the weeks, and then months, ticked by, the decaying corpses went from being a symbol of victory to a symbol of neglect.

Naib is not from Mosul. Like most others from the PMF, he hails from the south of Iraq, where Shiites are the majority. Naib represents a link in a chain of checkpoints that have defined Mosul’s streets since the U.S. invasion. Iraq’s Sunnis had dominated the government under Saddam Hussein, but that changed after 2003, and now Sunnis in Mosul feel neglected by the Shiite-dominated government in Baghdad. For years, they have seen the checkpoints in their city as a symbol of oppression by the majority Shiites. ISIS is now gone, but the checkpoints are back, many manned by soldiers who regard locals with suspicion. The feeling is mutual. Tensions did not disappear with the Islamic State.

Passing Naib’s checkpoint at an intersection in front of the church, Nineveh Street leads through the Old City back to Billah’s house. On the opposite corner is a mosque whose gardens have been appropriated as an impromptu graveyard. For families like Billah’s, for whom all the working men have died, their only assistance comes from the congregation, which pools donations and distributes them. “People know each other here. You know me, I know you. It’s like a family,” said Billah. “But everyone is poor here, even the mokhtar.”

Billah says the biggest change since ISIS fell is that women can walk on the street freely to go out and buy things. But there is barely a corner grocery store in the Old City, and apart from checkpoints, she doesn’t see the Iraqi state any more than she did during the Islamic State occupation. “Politicians never come here,” she said with annoyed cynicism. “The government is interested more in politics than in the citizens. They are interested in themselves.”

<--->

In the Greek myth of Pandora’s box, a woman named Pandora inadvertently opens a box that releases all of the evils out into the world. Out of the box fly fear, jealousy, anger, war, and all the pain that afflicts humanity. The last thing to fly out of the box is hope.

Greeks debated the meaning of the myth. Was hope a final mercy from the gods to allow humanity to survive all the other evils just released into the world? Or was hope — which kept the foolhardy from acknowledging reality — the ultimate evil?

Abulrahman, the mokhtar, says he has big plans for his neighborhood. He wants to build a school and library. He talks with his hands, painting vivid dreams in the air. “I really want the United Nations to participate and bring experts from America, Japan, or Germany who can do things like make gardens for the children, because the children should stop playing in rubble. It takes years to clear these experiences,” he said, gesturing around him.

But now, he is stuck in limbo waiting for funds. His work outweighs the power of his toolbox. He can patch up holes from bullets and shrapnel, but he can’t rebuild a whole house. Nor can he raise the spirits of an entire neighborhood that has suffered a deep collective trauma and doesn’t have the tools it needs to recover. “A human becomes a monster,” he contemplated. “That’s the problem, and that has made us anxious. People do their best to keep their situation stable. But psychologically, they are totally destroyed.”

A straight-talking pragmatist, Abdulrahman frames things in terms of problems and solutions. But being the village optimist of the neighborhood weighs on him, and his frank words betray a sense of unease. “The destruction has really hit hearts,” he said. “Spirits are down. They want to go back to what was before, but so much hate has been created.”

A few blocks away, at Um Zaman’s house, the streets are quiet. The sounds of hammering fade into the distance and the ground becomes harder to navigate. The fallen buildings and hills of collateral damage make the landscape look as though the war was yesterday. Her neighborhood does not have a mokhtar to help with rebuilding. She has lost enough to become cynical and dubious of the future.

“After a year or a month, nothing will change,” she said. She lives on the east side of the city now, with two young children who survived the war. She does not know how she will support them. “I just came to see things,” she said. “How could I live here?”

Her voice hard, she answered herself: “There is no way to.”