PARIS — It’s been four years since Mohammad Hijazi said goodbye to his mother and fled Syria. From a Damascus suburb where clashes still flare between government and rebel militias, she is able to call him every few days on Skype — whenever a diesel-powered generator or car battery is available to power up the Internet modem.

“We always hear explosions in the background, and sometimes they sound very close,” Mohammad, told Yahoo News. “It’s not safe in Syria.”

Now living in Paris, 28-year-old Mohammad spends his time at Le Daily Syrien, a trendy, turquoise-tiled restaurant in the 10th arrondissement, an Arab and North African immigrant neighborhood dotted with bars, cafés, halal butchers and grocery stores. He gets a familiar welcome from the owner and regulars, but still he is pensive and uneasy.

“I feel like a tourist here. Of course it’s a beautiful city, but it’s not beautiful when you’re forced to be here,” Mohammad said.

On Sunday, he watched tensely as French citizens headed to the polls to cast votes for either the independent centrist and political novice Emmanuel Macron or Marine Le Pen of the far-right National Front party in the political face-off that will determine his family’s future and whether his mother will be able to escape Syria to join him in Paris.

Le Pen’s pledge to end all immigration to France — both legal and illegal — places Mohammad among many thousands of Syrians whose families’ futures are at stake as French voters head to the polls Sunday to select their next president.

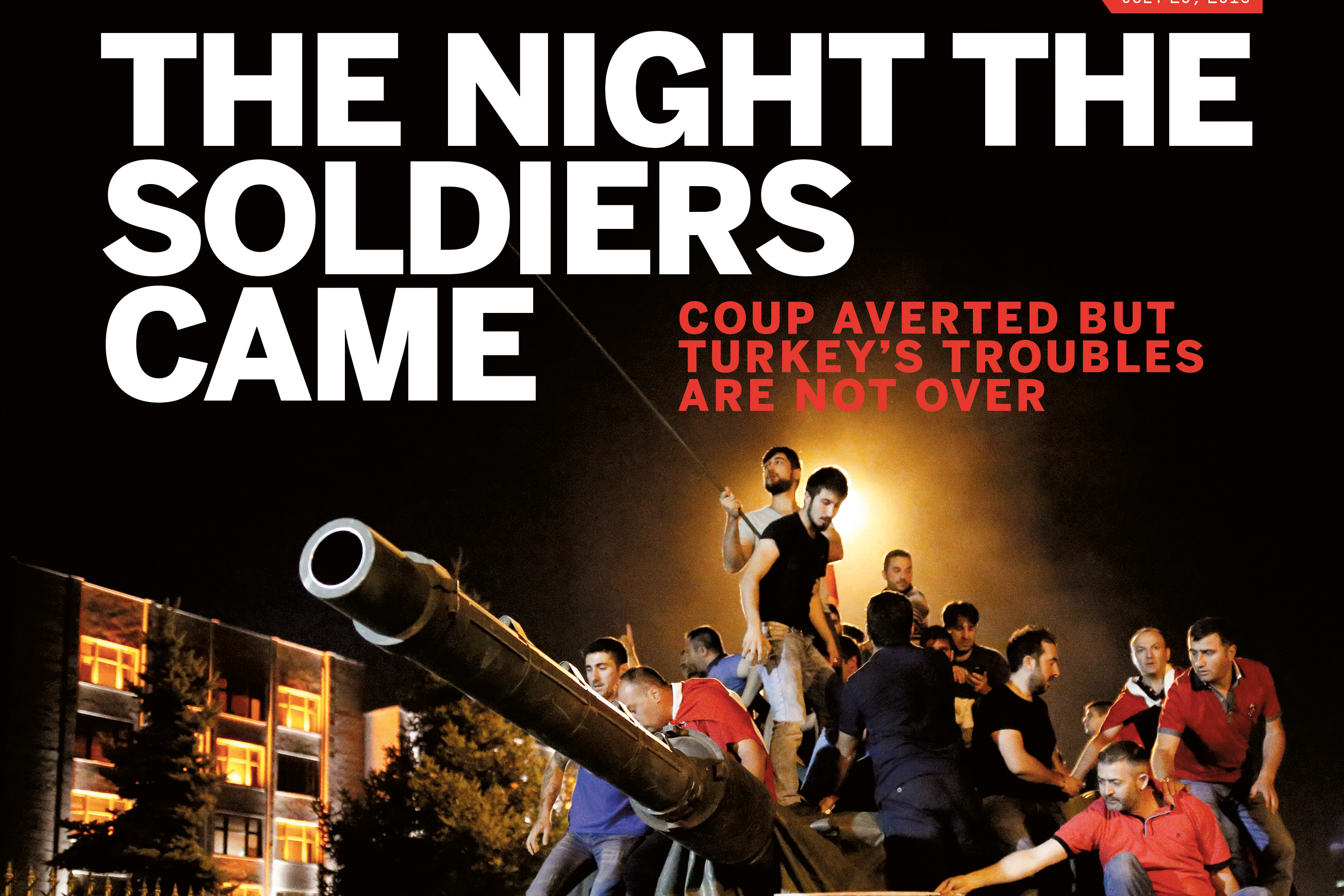

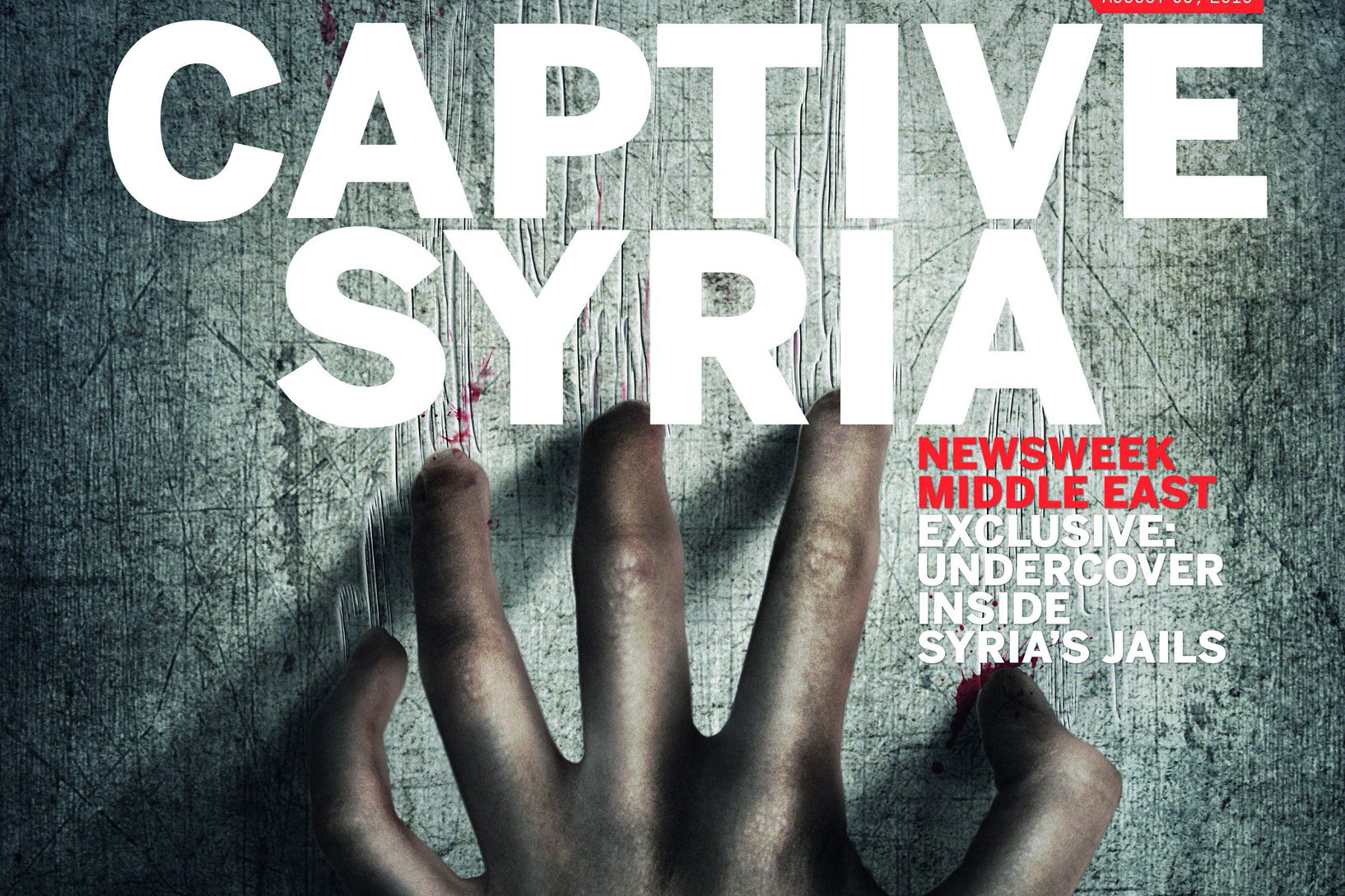

Before leaving his home country for France, Mohammad spent three months imprisoned by Syria’s brutal secret police, who exercise wide powers to jail anyone suspected of opposing the regime. He hesitates to talk about what happened there. In 2013, he managed to smuggle himself out and spent the next few years shuttling between Lebanon, Qatar, Jordan and Turkey, before finally being granted an asylum visa to join his sister in France earlier this year. Soft-spoken, introverted and still rattled from his experience, Mohammad is adjusting to Parisian life and exploring his talents as a graphic artist and filmmaker.

“I was so glad to have my brother back with me,” Anmar Hijazi, 32, told Yahoo News. “It’s a chance for him to do something, to express himself and create new opportunities for himself and for the world, not just be forgotten in war.”

Now reunited, the siblings say their only worry is finding a way for their mother (whose name they preferred withheld over concerns for her safety) to join them in France, but depending on the election results, that window of opportunity could soon close.

The current legal system allows two avenues: Anmar has been living in France since before Syria’s civil war began in 2011 and could be eligible to become a citizen in the next year, which would allow her to sponsor a visa for her mother. If Mohammad’s final asylum status is approved sooner, he will be able to apply for family reunification — a right recognized by the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.

More than 14,000 Syrians have received asylum in France since the war started in 2011, leading to the displacement of over 5 million people — or a quarter of the country’s population. Another 90,000 have been granted legal residency under EU regulations providing for family reunification.

The populist Le Pen whipped up campaign support with promises of dramatic tightening of the country’s refugee and immigrant policies. The National Front’s campaign platform, charged with nationalism and anti-EU rhetoric, promises to radically curb immigration and “restore France to the French.” If elected president, Le Pen has vowed to force the EU to reverse its open immigration policy, or otherwise call a Brexit-like referendum to pull France out.

fter France was rocked by ISIS terror attacks that came at the height of Europe’s refugee influx in November 2015, the National Front surged in early polling in regional elections on a wave of anger over EU immigration policies and campaigned to “protect the country” by halting immigration completely. Le Pen has since likened the rise in refugees to a “barbarian invasion” and vowed to cheering crowds to “send them home.”

Macron, for his part, has praised Germany’s response to the refugee crisis as having “saved Europe’s dignity.” In a fiery debate days before the election, Macron blasted Le Pen for “giving the jihadists exactly what they want:” a world of black and white where Muslims cannot coexist with the West.

“Confusing terrorists with asylum seekers and refugees is a profound moral, historical and political error,” Macron’s campaign wrote in an email this week.

Macron led Le Pen 24 percent to 21 percent after the first wave of voting two weeks ago. While a surprise victory akin to the U.K.’s Brexit vote or the stunning rise of Donald Trump in the U.S. is unlikely for Le Pen, Mohammad’s concern is less about her than the lingering sentiment among people with whom her anti-immigrant message is resonating.

“We are all afraid of Le Pen. As someone who suffers from all of the violence happening in Syria, I hate this kind of speech,” Mohammad says. Anmar jumps in with a laugh: “We’re Syrians, we’re not used to voting!”

Legislative elections to follow in June remain an important factor in determining how much power the new president will have to advance their agenda in Parliament, where a coalition government is a near certainty.

Until then, Mohammad and Anmar hold out hope that the system will work long enough for their mother to be granted a visa.

“We don’t know what [Le Pen] can do, but what I’m afraid of is people’s reactions in the streets,” Mohammad says, sipping a French espresso. “If she wins, the propaganda against immigrants won’t stop.”